In conversation with Gabriele Beveridge

“Visibility matters—when more women’s work is seen in public spaces, it’s an opportunity to stop someone still.”

- Gabriele Beveridge

Artist Gabriele Beveridge with NEST (II) at Glassed in Dreams exhibition private view at 100 Bishopsgate, London. Image credit Isabel Infantes PA Media Assignments.

Gabriele Beveridge is known for her sculptural and conceptual practice that combines materials as diverse as hand-blown glass, photo chemicals, and found images. Her assemblages put display on display, spotlighting the modular shelves that populate the innards of high-street shops, often combining them with slumped hand-blown glass forms that harness the material’s beauty, strangeness, and ubiquity. They mimic the body and the way it’s displayed in a vastly expanding search space, where biology evolves with the natural and non-natural, the organic and inorganic.

Your installation Glassed in Dreams at 100 Bishopsgate is truly captivating. Can you describe how you approached this site-specific installation and how the architecture of the space influenced your creative process?

Thank you. I grew up in Hong Kong and lived among glass towers, and my memories are full of the life Hong Kong had to offer. Markets springing up between skyscrapers. The humidity. The way life squeezes itself into every gap and corner. With this installation, I was thinking about living among those rigid geometries and the influence of sunlight and reflections. I wanted the glass to act as both a window and a membrane, capturing light and reflections to give the impression of something both solid and dissolving.

NEST (II) by artist Gabriele Beveridge at Glassed in Dreams exhibition private view at 100 Bishopsgate, London. Image credit Isabel Infantes PA Media Assignments.

What is it about glass that draws you in so intensely, and how does this material help communicate the ideas you’re exploring in your sculptures?

I’ve worked with glass for around 15 years. I was initially interested in it because it flows; it’s a liquid at one point, and then physically, how this fluidity becomes frozen. It is simultaneously fragile and strong, ancient yet continuously evolving. I’m fascinated by how it embodies transformation, both in its making and in its ability to alter the perception of a space. Take Nest, which almost filled my studio at one point. It’s a cube of glass with eight transparent pink orbs, or organs I call them, at its core. As you walk around it, you can see the reflection of these glass orbs transposed into the empty space, which plays with the idea of who is observing whom. In fact, one night I came back to my studio, and the moon was shining through the skylights onto Nest, and it created gridlines and abacus-like shadows throughout the space, as if it was computing or broadcasting.

In a corporate space like 100 Bishopsgate, do you think public art can influence the atmosphere and daily interactions among employees and visitors?

I hope it can. I certainly take inspiration from the city and daily life, the psychological charge of the street. Public art can work if it interrupts the expected rhythms of daily work life. This installation Glassed in Dreams was conceived to offer a pause, a chance to see something shift in the glass as people move past it.

Incorporating poetry, particularly George Oppen’s Of Being Numerous, seems to be a key influence in your work for this project. How do you see the relationship between poetry and sculpture, and how does Oppen’s poem inform the sculptures displayed in Glassed in Dreams?

Poetry and sculpture both have a way of distilling experience. And maybe it’s a similar instinct to search blindly, grasping at meaning like water through fingers. There’s probably less room for experimentation with glass because you sort of need to know what you’re doing before you make it, but the more you work with it, the more you get to know its tension and rhythm, the colours it takes, and the happy accidents that can lead on to the next thing. I also think Oppen’s Of Being Numerous speaks to the tension between the organic and inorganic, which is an idea in my work. And there are moments in his poem where he sets up an image to stand in its own right: something that is so independent that it is “patient with the world.”

As a female artist involved in a project to boost the visibility of women sculptors, how does it feel to challenge the gender imbalance in public art spaces?

Large-scale sculpture and public art have been male-dominated fields, yes, and that imbalance is still very present today. Visibility matters—when more women’s work is seen in public spaces, it’s an opportunity to stop someone still.

What is next for you in terms of exploring new materials, themes, or spaces in your future projects?

I’m currently experimenting with materials that push the boundary between the natural and the engineered—working with metal mesh and light-responsive coatings. Site-wise, I’m drawn to working in outdoor environments where the natural elements—wind, water, changing light—become active participants in the work. I realised while walking through a solo show recently, that so much of my recent work arrests chaotic elements in nature and brings them into view. Whether it’s chemicals on anodised aluminium panels that look like they’re being influenced by electromagnetic waves or cosmic patterns on marble, I’m working with rough materials, but it’s also a bit like developing a photograph in a darkroom. I heard a nice line recently by the chemist Lee Cronin: “life is the universe developing a memory.” That makes sense to me.

BODIES (I,II) by artist Gabriele Beveridge at Glassed in Dreams exhibition private view at 100 Bishopsgate, London. Image credit Isabel Infantes PA Media Assignments.

The [Quick] #FLODown:

Best life advice?

Follow the beauty.

Last song you listened to?

Laurens Walking by Angelo Badalamenti.

Last book you read?

Breath of Life by Clarice Lispector.

Can't live without...?

Cigarettes.

What should the art world be more of and less of?

Less of a silo.

Glassed in Dreams, a free large-scale, female-led sculptural installation, by Gabriele Beveridge is on display at 100 Bishopsgate until February 2026. Created in collaboration with curatorVassiliki Tzanakou, the project was selected as the winning commission of the Of Being Numerous open call. Presented by Brookfield Properties and AWITA, this cultural initiative champions underrepresented female talent in a city where only 13% of sculptures are attributed to women.

A parallel exhibition, ‘Inside the Studio: How Artists Make Work’, at Brookfield Properties' 30 Fenchurch Street, showcases Beveridge's winning submission alongside notable proposals from three of the +40 artist-curator duo's entries of the 'Of Being Numerous' open call, offering insight into the creative process behind public sculpture commissions and placemaking.

Website: gabrielebeveridge.com

Instagram: @gabrielebeveridge

Peter Bellerby is the founder of Bellerby & Co. Globemakers, a company renowned for its exquisite hand-crafted globes. Established in 2010, the company specialises in meticulously designed pieces that showcase exceptional craftsmanship, positioning Bellerby & Co. as a leader in the globe-making industry…

Gabriele Beveridge is known for her sculptural and conceptual practice that combines materials as diverse as hand-blown glass, photo chemicals, and found images…

Robyn Orlin is a South African dancer and choreographer born in Johannesburg. Nicknamed in South Africa "a permanent irritation", she is well known for reflecting the difficult and complex realities in her country. Robyn integrates different media into her work (text, video, plastic arts) to she investigates a certain theatrical reality which has enabled her to find her unique choreographic vocabulary…

Katrina Palmer, an artist known for exploring materiality, absence, and dislocation, recently spoke to us following her year-long residency at the National Gallery about her exhibition The Touch Report…

Enej Gala is an artist who splits his time primarily between London and his hometown of Nova Gorica, Slovenia. A graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice and the Royal Academy Schools (2023), Gala first gained our attention with Neighbour’s Harvest, an installation that cleverly combined puppetry and conceptual art…

David Ottone is a Founding Member of Award-winning Spanish theatre company Yllana and has been the Artistic Director of the company since 1991. David has created and directed many theatrical productions which have been seen by more than two million spectators across 44 countries…

Darren Appiagyei is a London-based woodturner whose practice embraces the intrinsic beauty of wood, including its knots, cracks, bark, and grain. Highly inspired by Ghanaian wood carving, Darren explores raw textures and new woods in his work…

Huimin Zhang is an artist specialising in 22K gold, known for her innovative craftsmanship. She combines various cultural techniques, including filigree, engraving, and European gold and silver thread embroidery, to create unique works…

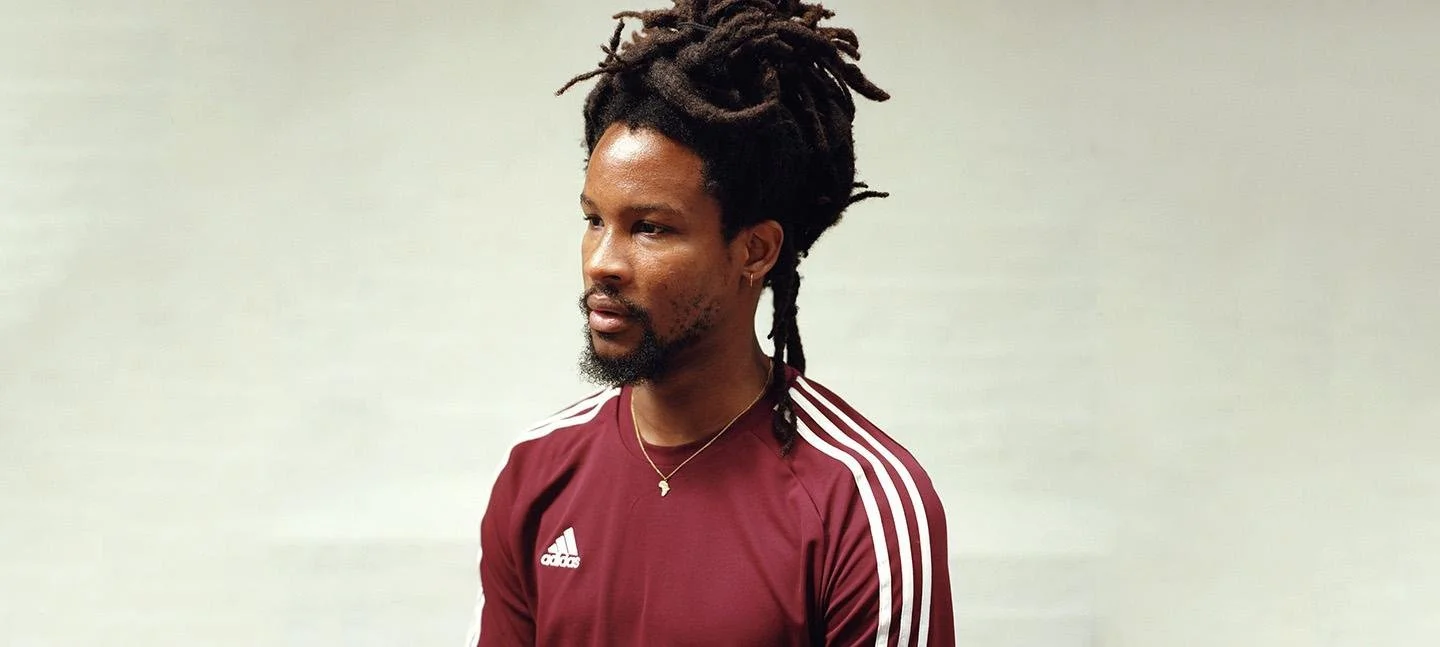

Akinola Davies Jr. is a BAFTA-nominated British-Nigerian filmmaker, artist, and storyteller whose work explores identity, community, and cultural heritage. Straddling both West Africa and the UK, his films examine the impact of colonial history while championing indigenous narratives. As part of the global diaspora, he seeks to highlight the often overlooked stories of Black life across these two worlds.

Hannah Drakeford is a London-based interior designer known for her bold and colourful interiors. She transitioned from a 21-year retail design career to interior design, and has gained popularity on social media where she now shares creative upcycling tutorials and encourages individuality in home decor…

Shula Carter is an East London-based creative with a background in contemporary, ballet, and modern dance. She trained at the Vestry School of Dance and later at LMA London, where she developed skills in commercial, hip hop, and tap dance, alongside stage and screen performance…

Dian Joy is a British-Nigerian interdisciplinary artist whose work delves into the intersections of identity, digital culture, and the fluid boundaries between truth and fiction. Her practice is rooted in examining how narratives evolve and shape perceptions, particularly in the digital age.

Dian Joy is a British-Nigerian interdisciplinary artist whose work delves into the intersections of identity, digital culture, and the fluid boundaries between truth and fiction. Her practice is rooted in examining how narratives evolve and shape perceptions, particularly in the digital age.

John-Paul Pryor is a prominent figure in London’s creative scene, known for his work as an arts writer, creative director, editor, and songwriter for the acclaimed art-rock band The Sirens of Titan…

Jim Murray is an actor, director, conservationist and artist known for Masters of Air (2024) and The Crown (2016). Murray first came to prominence as an artist in 2023 with his acclaimed inaugural exhibition In Flow, where his dynamic abstract paintings were hung in conversation with John Constable’s The Dark Sid…

Anthony Daley is an abstract expressionist painter known for his vibrant, large-scale works that explore beauty through intense colour and light. His art bridges the past and present, drawing inspiration from the Old Masters as well as diverse sources like literature, science, poetry, and nature.

Rachel Kneebone’s work explores the relationship between the body and states of being such as movement, stasis, and renewal. Through her porcelain sculptures, she examines transformation and metamorphosis, reflecting on what it means to inhabit the body and be alive…

Saff Williams is the Curatorial Director at Brookfield Properties, bringing over fifteen years of experience in the arts sector…

Sam Borkson and Arturo Sandoval III, the acclaimed LA-based artists behind the renowned collective "FriendsWithYou," are the creative minds behind "Little Cloud World," now on display in Covent Garden. During their recent visit to London, we had the privilege of speaking with them about their creative process and the inspiration behind this captivating project.

Kinnari Saraiya is a London-based Indian artist, curator, and researcher whose work focuses on trans-altern and post-humanist ideas from the Global South. She is currently a curator at Somerset House and has held positions at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Frieze Art Fair, and Bowes Museum....

Fusing her Asian roots with a fascination for African pattern work and her deep passion for architectural geometry, Halima’s work is intense yet playful, structured yet creative; substantial yet dynamic and invariably compelling in its originality.

Matilda Liu is an independent curator and collector based in London, with a collection focusing on Chinese contemporary art in conversation with international emerging artists. Having curated exhibitions for various contemporary art galleries and organisations, she is now launching her own curatorial initiative, Meeting Point Projects.

EKLEIDO, a choreographic duo formed by Hannah Ekholm and Faye Stoeser, choreograph performances for live shows and film.

Lydia Smith is one to watch. Currently on show in three different places across London, her work can be seen in a solo exhibition in the City, a group show in a chapel in Chelsea and through a new series of monumental sculptures installed outdoors across sprawling parkland…

Taipei-based IT entrepreneur Elsa Wang is the founder of Bluerider ART, a progressive gallery at the intersection of art and technology.

Jemma Powell is known for her observational landscapes. She is also an accomplished actress having featured in Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland…

Suzanna Petot, originally from New York, is a curator and writer based in London. She holds an MA in Curating the Art Museum from The Courtauld Institute of Art and has worked at various institutions in the U.S., Italy, and the UK, including Gallerie delle Prigioni, The Courtauld Gallery, Tate Modern, M.I.T List Center for Visual Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art…

Deep K Kailey boasts a highly successful career in the fashion industry, having made significant contributions to renowned publications such as Dazed, Vogue, and Tatler. However, driven by a quest for deeper meaning in life, she embarked on a transformative spiritual journey. This path ultimately led her to establish one-of-a-kind arts organisation Without Shape Without Form (WSWF)….

Elli Jason Foster and Millie Jason Foster are the dynamic co-directors behind Gillian Jason Gallery. This groundbreaking gallery is the first of its kind in the UK, wholly committed to celebrating female artists…

Megan Piper is the co-founder and Director of The Line, a public art project in east London, established in 2015. Prior to setting up The Line, she had a gallery in London’s Fitzrovia, where her exhibition programme focused on rediscovering and re-evaluating artists whose careers started in the 1960s and 70s…

What’s On in London This Week: Discover rooftop games at Roof East, cherry blossoms at the Horniman Gardens, and Easter fun at Hampton Court Palace. Plus, catch Loraine James live, Dear England at the National Theatre, and jazz nights at Ladbroke Hall…

London is set to showcase a rich and varied programme of art exhibitions this May. Here is our guide to the art exhibitions to watch out for in London in May…

With summer around the corner, what better way to spend a sunny day than by enjoying art, culture, and a bit of al fresco dining? Whether you’re looking for a peaceful spot to reflect on an exhibition or simply want to enjoy a light meal in the fresh air, here’s our guide to some of the best museum and gallery cafés with outdoor terraces in London….

As summer arrives in London, there’s no better time to embrace the city’s vibrant outdoor dining scene. Here is our guide to the best outdoor terraces to visit in London in 2025 for an unforgettable al fresco experience…

Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2025 · Gabriel Moses: Selah · Eileen Perrier: A Thousand Small Stories · Dianne Minnicucci: Belonging and Beyond · Linder: Danger Came Smiling · The Face Magazine: Culture Shift · Cecil Beaton’s Fashionable World · Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2025 · Photo London 2025 · Taylor Wessing Photo Portrait Prize · Nature Study: Ecology and the Contemporary Photobook · Flowers – Flora in Contemporary Art & Cultur…

This April, Ladbroke Hall’s renowned Friday Jazz & Dinner series returns, showcasing an impressive roster of artists at its Sunbeam Theatre. Each evening pairs exceptional live jazz with a carefully crafted menu from the award-winning Pollini restaurant…

Holly Blakey: A Wound with Teeth & Phantom · Kit de Waal: The Best of Everything · Skatepark Mette Ingvartsen · Spring Plant Fair 2025 · Hampton Court Palace Tulip Festival 2025 · Loraine James – Three-Day Residency · Jan Lisiecki Plays Beethoven · Carmen at The Royal Opera House · Cartier Exhibition · The Carracci Cartoons: Myths in the Making · Nora Turato: pool7 · Amoako Boafo: I Do Not Come to You by Chance · Bill Albertini: Baroque-O-Vision Redux…

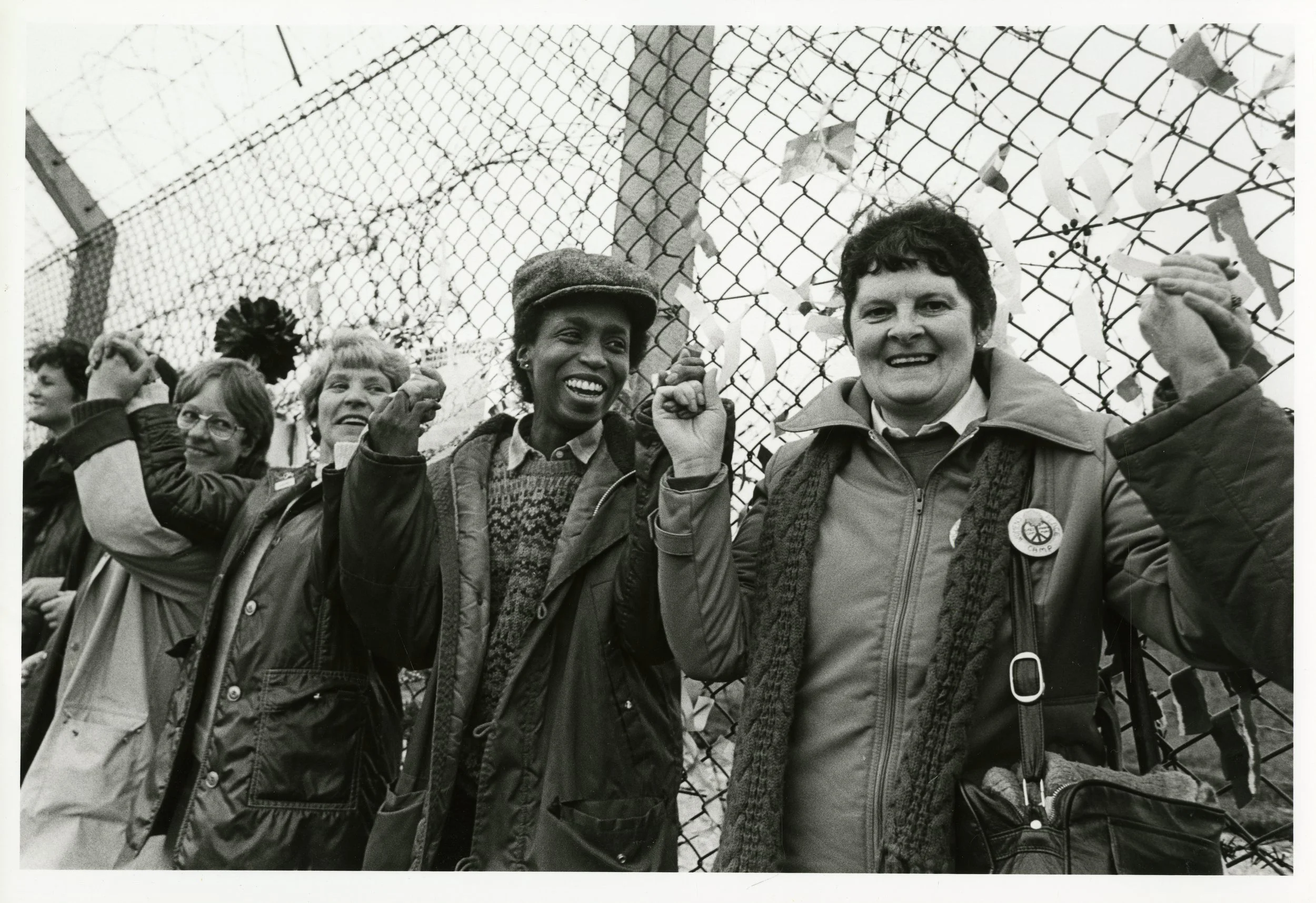

Robyn Orlin had her first encounter with the rickshaw drivers of Durban at the young age of five or six, an experience that left such a deep impression on her that she later sought to learn more about their fate. Rickshaws were first introduced to Durban in 1892…

Murder She Didn’t Write is misbehaviour live on stage peppered with self-awareness and unbelievably good writing. This isn't a fad, this isn't sloppy - it’s naughty and scathingly witty…

TOZI, derived from the affectionate Venetian slang for “a close-knit group of friends,” is the brainchild of an Italian trio that met while opening Shoreditch House under the Soho House Group. In 2013, Chef Maurilio Molteni, fresh from his time as Head Chef at Shoreditch House and developing the menu at Cecconi’s, opened the first TOZI restaurant in London…

Multitudes at Southbank Centre will reimagine live music through bold collaborations across dance, theatre, and visual arts…

Multitudes Festival · Ed Atkins, Tate Britain · Brick Lane Jazz Festival · Teatro La Plaza’s Hamlet · Holly Blakey: A Wound with Teeth & Phantom · Roof East · Hampton Court Palace Tulip Festival 2025 · London Marathon 2025 · ROOH – Within Her · Sultan Stevenson Presents El Roi · Carmen at The Royal Opera House · The Big Egg Hunt 2025 · Architecture on Stage: New Architects · The Friends of Holland Park Annual Art Exhibition 2025

Autumn 2025 will bring two exciting exhibitions to the Barbican: ‘Dirty Looks’, a bold fashion exhibition exploring imperfection and decay, and an innovative art installation by Lucy Raven in The Curve…

Robyn Orlin: We wear our wheels with pride · Architecture on Stage: Lütjens Padmanabhan · Jay Bernard: Joint · Black is the Color of My Voice · Joe Webb Trio · Rhodri Davies at Cafe OTO · Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award 2025 · Lyon Opera Ballet: Cunningham Forever · AVA London · Sister Midnight · Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo · Eunjo Lee · Arpita Singh: Remembering · Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press: Disarm · Bunhead Bakery · Time & Talents

Looking for something truly special this Mother’s Day? There are a variety of unique gifts and experiences to take advantage of in London, whether your mother loves exploring world-class art galleries and museum exhibitions, wandering through historic homes filled with fascinating stories and remarkable collections, indulging in a luxurious spa treatment, or enjoying an unforgettable dining experience..

After 18 successful years at Edinburgh Fringe, The Big Bite Size Show arrives in London for the first time at The Pleasance Theatre, no less. A gem of a place for fringe theatre in London…

180 Studios will present the largest showcase of photographer and filmmaker Gabriel Moses’ work to date, featuring over 70 photographs and 10 films in March…

Cartier Exhibition at the V&A · Giuseppe Penone: Thoughts in the Roots · Antony Gormley: WITNESS · Richard Wright at Camden Art Centre · The Carracci Cartoons: Myths in the Making · Eileen Perrier: A Thousand Small Stories · Ed Atkins at Tate Britain · Richard Hunt: Linear Peregrination · Nolan Oswald Dennis at Gasworks · Nora Turato: pool7 · In House: Ree Bradley and Pete Gomes at Studio Voltaire…

The Shirley Sherwood Gallery of Botanical Art at Kew Gardens will showcase new botanical works, cinematic installations, and the connections between artists and trees…

Orchid Festival · Alice Sara Ott: John Field & Beethoven · Our Mighty Groove at Sadler’s Wells East · Seth Troxler at Fabric · North London Laughs – A Charity Comedy Night · London Symphony Orchestra: Half Six Fix – Walton · In Focus: Amir Naderi · Artist Talk: Citra Sasmita - Into Eternal Land · Noah Davis at Barbican · Theaster Gates: 1965: Malcolm in Winter: A Translation Exercise · Ai Weiwei: A New Chapter · Galli: So, So, So · Somaya Critchlow: The Chamber

The Cinnamon Club had completely flown under the radar for me. It is in a pocket of London I rarely visit, and even if I did, the building’s exterior gives little indication of what’s inside. But now that I’ve discovered it, I already have plans to return with my husband - and in my mind, a list of friends I would recommend it to…

An important exhibition has opened at the National Gallery co-organised with the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Mayor of Siena, Nicoletta Fabio was in attendance on opening day to mark the exhibitions significance. Normally a major exhibition would take two to three years to come to fruition, in this instance, it has been in the making for eight year…

Máret Ánne Sara to create 2025 Hyundai Commission as Tate and Hyundai extend partnership to 2036.

Claudia Pagès Rabal: Five Defence Towers · Tirzah Garwood: Beyond Ravilious · Heather Agyepong: Through Motion · Christina Kimeze · Citra Sasmita: Into Eternal Land · Mire Lee: Open Wound · Linder: Danger Came Smiling · Galli: So, So, So · Mickalene Thomas: All About Love …

Marylebone Village to host a week of events championing female founders and entrepreneurs, including a panel discussion and fundraising for the Marylebone Project…

Battersea Power Station will host Good Fit, a month-long event featuring workouts, mindfulness sessions, expert talks, and wellness experiences…

Trisha Brown Dance Company & Noé Soulier – Working Title & In the Fall · (LA)HORDE / Ballet National de Marseille – Age of Content · Lyon Opera Ballet – Merce Cunningham Forever (BIPED and Beach Birds) · Neither Drums Nor Trumpets – Pam Tanowitz · Robyn Orlin – We Wear Our Wheels with Pride