In conversation with Akinola Davies Jr

“…for as long as I can remember, I’ve really enjoyed being a witness to culture, being a witness to my surroundings, and observing how things are done.”

- Akinola Davies Jr

Akinola Davies Jr. Courtesy of the artist.

Akinola Davies Jr. is a BAFTA-nominated British-Nigerian filmmaker, artist, and storyteller whose work explores identity, community, and cultural heritage. Straddling both West Africa and the UK, his films examine the impact of colonial history while championing indigenous narratives. As part of the global diaspora, he seeks to highlight the often overlooked stories of Black life across these two worlds.

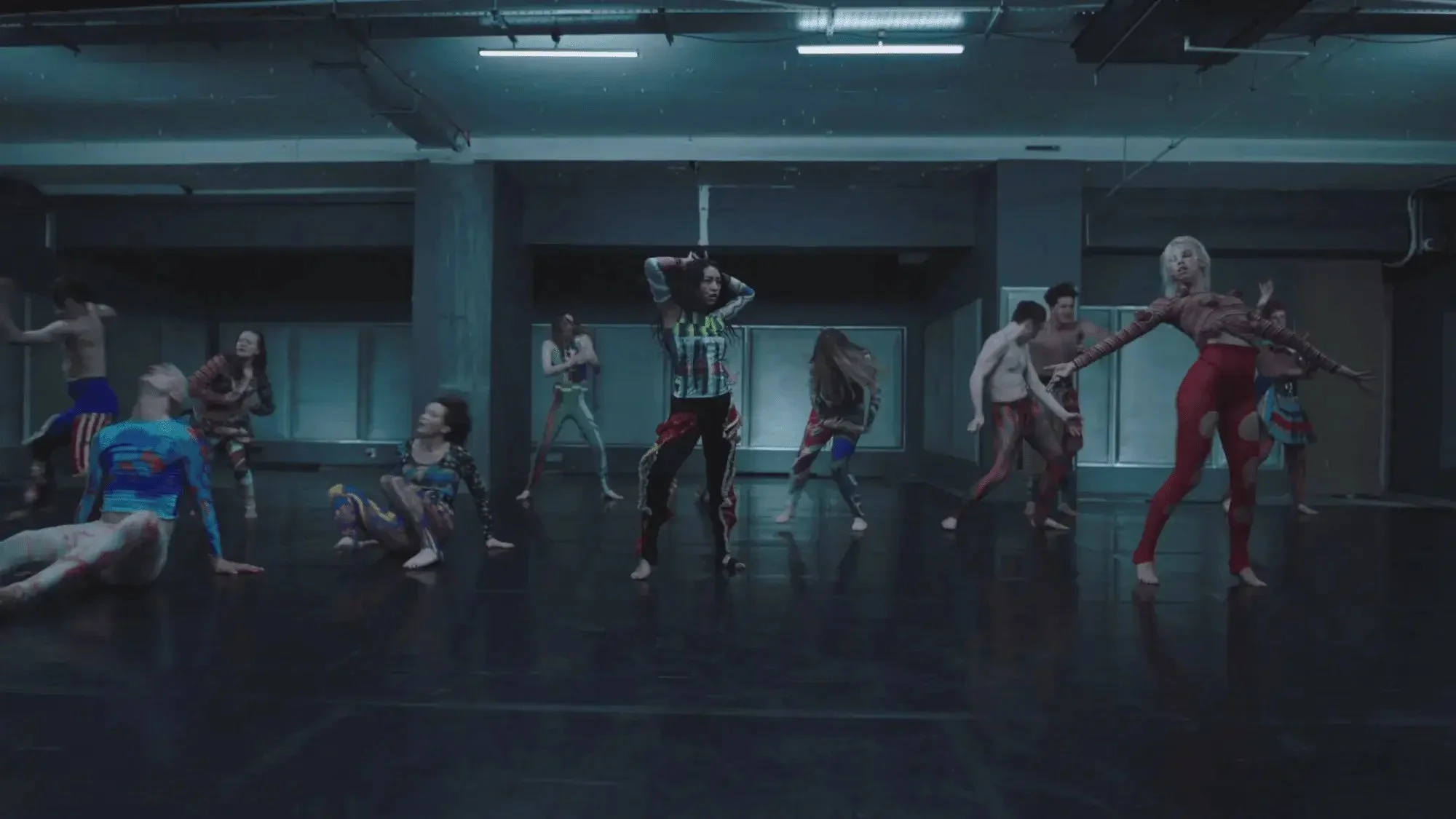

As part of Somerset House’s 25th-anniversary celebrations, Davies will premiere Rituals: Union Black during the Summer Series. The project honours the collective resonances of Black British communities, documenting the everyday rituals that define their rhythms of life. The film will also feature a specially commissioned live score, performed by an incredible lineup of contemporary musical talent.

We had a chat with him ahead of the premiere to discuss his creative process and the inspirations behind the project.

Your latest commission for Somerset House explores the rhythms and rituals of Black life in the UK. How much did your upbringing in Lagos and its traditions influence this project?

To be completely honest, I don’t really think that my upbringing in Lagos has much of anything to do with this project. I guess the only similarity would be a sort of resonance with history because this project is about archiving, and I guess if we were thinking back to my upbringing, there are things and tapestries of the world I like to sort of archive because I think it’s quite important.

But I don’t think that my upbringing in Lagos has any influence on this project. More so, this project is influenced by wanting to be of service to my community, by trying to understand it a bit more, by trying to see more diversity within the community—which is Black life across the UK, and it exists in so many forms. I think that what should be honoured is the day-to-day of that life.

Did your passion for storytelling and the arts come naturally, or was there a defining moment in your life that set you on this path?

I don’t know… that’s kind of a hard question. I think for as long as I can remember, I think James Baldwin said something about being a witness, and for as long as I can remember, I’ve really enjoyed being a witness to culture, being a witness to my surroundings, and observing how things are done.

I think Nigerians, and Africans in general, are master orators. I know my mom is a great one. She used to tell really fantastic stories over and over again, so maybe in that sense, it feels like that was something I was exposed to quite early on.

I mean… I don’t really know what the defining moment is. I guess it’s just the moment where I decided I was going to pursue film and storytelling with that medium because previously, I wanted to be a journalist. I didn’t know really how or when or with whom this would be achieved, but I decided I was committed to making films.

Your short film Lizard, which explores themes of innocence, power, and danger through the eyes of a young girl in Lagos, won the Sundance Grand Jury Prize and earned a BAFTA nomination. What did that recognition mean to you personally, and how did it influence the direction of your work moving forward?

I mean, I guess on the one hand, it kind of acknowledged the fact that stories from different parts of the world are of value and can be presented in a way that has a sort of generality to it.

I’m hesitant to say it’s all about me, as I think the reality of the situation, what it really reminded me of, is the power of being able to work at home and with local technicians, and what people in Nigeria are capable of if we all work together and if we are empowered to tell the stories in a way that we wanna tell them, that feel real to us.

I’m not sure how it influenced my work, but I think I’ve always been obsessed with the process of making films more so than the execution. The process is something that really needs to be protected, and it’s something that needs to be really worked at because once that process is sort of watertight, it’s a good springboard to be able to tell more stories.

I guess for me, the recognition reminded me that the process of development, all the notes and the scrutiny that you put a project under, is really important. The people who are working on that should feel invested in what they’re doing. And if they do feel invested in what you’re collectively doing, I think that’s the biggest influence.

Looking back at your career, is there a project that feels especially personal or meaningful to you? What made it stand out, and how did it shape your approach to storytelling?

I mean, to be honest, all of my projects have been pretty personal and meaningful to me. It’s hard to pick one from the other.

The film I made with Klein, Marks of Worship, was quite pivotal at that time when I sort of first started. This Hair of Mine with Cyndia Harvey was pretty instrumental in so many ways. The project I did with BBC about Black existence in Tudor times was again pivotal. Some stuff in fashion was quite big for me… I mean, there’s too many to account for.

I can’t really choose. It’s like asking someone what their favourite child is. I think all of those moments are really interlinked, so it’s quite hard to separate them. I’m grateful for all the films I’ve made because they’re all personal and meaningful to me. Each film, you just give a little bit more of yourself and learn a little bit more about yourself.

I think that’s what excites me about almost everything I’ve made—not so much the technical execution or the execution itself, but the process. Trying to understand the process is super important for me.

You’ve worked in film, fashion, and music. How do these different mediums complement one another in your work, and what keeps you moving between them?

I mean, I’m obsessed with film. I’m obsessed with the medium of film. I’m obsessed with the format.

They all have challenges, and they’re all extremely tricky, but ultimately, I think for me personally, it’s important to stay engaged and excited by the process of filmmaking. And each medium continues to innovate, each medium allows you to test and try things, to meet and work with people who you might not have considered in another medium.

All those things kind of work together, and I think for me, they’re quite important—to not have to choose one over the other. I think all those formats are something that I really enjoy and something that I’d like to keep doing for as long as possible.

We are looking forward to the debut of your 2025 Somerset House commission, which pays tribute to the collective resonances of Black British communities, set to debut as part of the Summer Series in celebration of 25 years of Somerset House as a cultural space. In what seems like quite a huge undertaking, how did you approach translating these everyday moments into film?

Well, the conception of this idea came from an intention to sort of expand and define what this community is. To really get away from what could be considered like a monolithic expression of blackness. What it means to be a black person in the UK. I’m obviously a particular type of black person in the UK, being first or second generation British African, which always pushes me to think about the tapestries of daily life. I think about what happens in the media – and it’s not necessarily a bad thing – but there’s a lot of focus on being exceptional. There’s a lot of focus on sports, music, dance, on all the extremities of black life in many ways. And when I was younger, I felt like I was one of those in-between kids who was never too great or never too bad, and maybe somewhere in there didn’t feel seen.

I think breaking that into a macro level, and you think of London being kind of where you see the extremities of black life, whereas there are so many areas and pockets in the UK where Black people live, and flourish, and exist, and have difficulties, but equally have a lot of successes. And I think a lot of this project is in honour of that. It’s in honour of the narratives that maybe don’t necessarily get pushed forward, even within the community. I think it’s really important that we understand that the black experience in the UK is interlinked and interwoven with each other. And just because London has a monopoly on visibility, it doesn’t mean there isn’t so much happening in the rest of the UK. It’s really important to also see how those experiences are shaped.

We talked about focusing a lot on the mundane, about focusing on everyday rituals – which is why the film is called Rituals: Union Black. We wanted to really honour the simple things without any pomp or fuss. We just really wanted to go and meet people as they are and document their lives as they are. I think there’s so much value in not dressing things up for the camera, but just seeing the reality of life.

With a specially commissioned live score accompanying the premiere, how does music bring an added layer of meaning to the project?

I guess similar to the question where you ask me about working with film, fashion, and music. It’s just an opportunity to bring all of my interests together. London has an extremely beautiful flourishing electronic, experimental, and jazz scene. It has all these young brilliant artists, and I think they’re all people I’ve always had dreams of collaborating with, ever since I’ve been familiar with what they do. And this felt like an opportunity for them to work on something that is just completely emotive, completely free of inhibition. I really enjoy creating a framework for people to just be free and express themselves through the themes of what they see, and not really having to second-guess themselves but really just put a stamp on what we’re watching.

And I think music really is the lubrication for everything. It’s a big driving force behind these films. It always has been, and I think I’m excited to have a live score, I’m excited for the people to hear them and to hear the renditions that could be different from what they are. All the composers who were involved were really generous with their time and really bought into the project, really bought into the commission from the start. There is just a lot of gratitude to a lot of them because I think from the get-go they’ve all expressed wanting to be involved and I’m just really excited to see how that shapes up.

What do you hope audiences will feel or reflect on when they watch this film?

I find this question divisive in a way…I don’t really wanna answer that. I’m interested in the dialogue. I’m interested in what comes back, not necessarily what I want people to see. I want people to see whatever they see in it and then I wanna hear what comes back. I think I don’t want to be derivative like “this is my expectation of it.” I just want to have a dialogue with the audience, I want to know what they see. I want to know how they feel when they see it. I want them to tell me what they like and what they don’t. I’m not really trying to push what I want people to feel or reflect. I just want to show how fortunate I’ve been to work with all these collaborators across the UK who’ve given us their time and who have given us access to their lives. Who’ve been really patient with us over the last 2/3 years whilst this project has been coming to fruition.

You know, I think these people who have so generously given us the honour to be able to document moments in their lives, it’s quite rare. I just don’t wanna put any impositions on that. I just want to see what people see.

Looking back, is there one moment in your career that stands out as particularly fulfilling or life-changing?

I don’t know, my career is still in its infancy so I don’t really know how to answer that. I mean, ask me again 10/20 years.

As you continue to grow as an artist, are there new themes or stories you’re eager to explore in the future?

Oh yeah, there’s loads to explore. I mean, if we just talk about the series, which is like an ethnographic series, I would love to continue and do it in other places in the UK that I never got to go to. I’d love to take it to Europe and different European countries. I’d love to take it to the Americas, to South America. I’d love to take it to Southeast Asia. I’d love to take it to East Asia. I’d love to do it around the continent. There is so much room for a project like this to expand, and I would really love for that to happen, whether it’s immediately or whether it’s in a matter of time. You know, I think archiving the daily lives of people is really important.

The [Quick] #FLODown

Best life advice?

If you wanna change the world, draw a circle around yourself and work on everything within that circle for the rest of your life, and that’s how you change the world.

Last song you listened to?

I was just listening to Favorite Mistake by Giveon in the car just a few minutes ago.

Greatest film?

There is no such thing. But if I had to pick one film that I think is magnificent, I would say Moolaadé by Ousmane Sembène. I think it was way ahead of his time when it was made, and it’s still incredible to this day.

Last book you read?

The last book I read was The Palm-Wine Drinkard by Amos Tutuola. It’s Nigerian folklore.

Can’t live without…?

I can’t live without taking long vacations and a lot of rest and sleeping eight hours or as much as possible.

What should the art world be more of and less of ?

Boy… I don’t know how to answer that question. To be honest… I mean, the world is quite an ambiguous term to begin with, but yeah, I don’t really know.

Website: akinoladaviesjr.com

Instagram: @akinoladaviesjr

LinkedIn: akinola-davies-jr