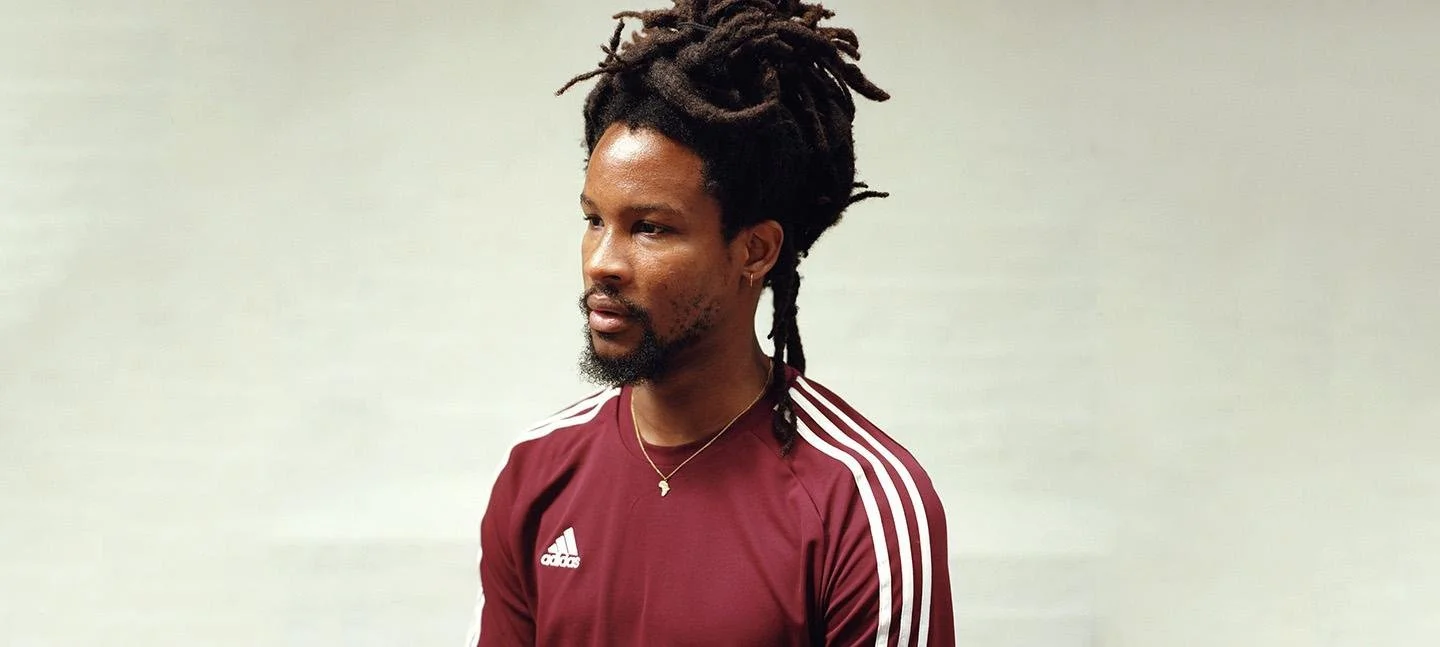

In conversation with Dian Joy

“I make work to create spaces for the audience to locate themselves within the research.”

- Dian Joy

Dian Joy.

arebyte Gallery is a hidden gem, located on London City Island – a place many Londoners, it seems, have barely heard of. But it’s so easy to get to and well worth a trip. arebyte is a refreshing change from the traditional style of gallery you might find in Mayfair, much as we love them, and their current show is a prime example. Alexandria’s Genesis is an exhibition by British-Nigerian interdisciplinary artist Dian Joy, which takes its title from an internet myth.

The myth of Alexandria's Genesis – once relegated to the obscure corners of the internet – has circulated on online forums and social media, evolving into many forms. A rumoured genetic anomaly, transforming people into long-living “perfect human beings” with violet eyes and flawless pale skin, gave those with the condition strength and vitality. Circulating online since 1998, the conspiracy was created by “Daria” fanfic writer Cameron Aubernon to explain her too-perfect female characters, gaining traction and spreading widely until it was eventually medically debunked. This sticky narrative, told as an illusory truth, offers a seductive deception of genetic superiority – a story that blurs the line between desire and reality, shaping perceptions of identity and feeding fantasies of perfection that favour youth, shimmering white skin, lack of hair beyond what was there at birth, perfect bodies and purple eyes.

Operating in the dystopian struggle between disinformation and information, fake and real, Alexandria’s Genesis explores how reality may be mutated, augmented and propagated by any means possible. At its core, it is a study of the social life of ideas, in the digital age. Dian Joy was such a pleasure to talk to – somehow she has taken some pretty wild concepts, and sometimes heavily academic notions, and created from that an environment that is immersive and totally engrossing.

The show runs until this Sunday 12 January, closing with a series of discussions and panel talks on the 11th. Don’t miss it!

How did you begin your journey into art? Did you grow up in a creative environment?

I grew up on an estate in London, just a stone's throw away from the Tate Britain. Although my immediate environment wasn’t explicitly creative, this proximity to the Tate afforded me countless school trips and rainy afternoons amongst its collection. My journey into art practice, however, is admittedly an odd and very much incidental story. In 2015, I moved to Amsterdam to attend university, primarily because it was much cheaper than studying in the UK during the pre-EU-exodus era. That year, through a series of unexpected events, I became a caregiver for a tabby cat called Bertje. When it came time to find him a permanent home, I wrote a Facebook post in search of his new guardian, which was answered by an artist called Melanie Bonajo. We struck up a friendship, and they invited me to collaborate with them as a performer. From there, my interest in art practice grew, and in 2017, I co-founded a collective called BLUE with friends across the globe who also felt compelled to explore exhibition-making. Working primarily over the internet, we came together to do things we could not imagine being able to do without each other's support. Many of these people are still practising today and doing incredible things, such as Arna Beth, Dyrfinna Benita, and Sofi Winther Foged.

How about your more formal education?

I did my BA in Liberal Arts and Sciences at Amsterdam University College, where I mainly focused on courses in the Film Theory, Cultural Studies, and Art Theory departments. While studying there, I developed a research specialism in the intersection of Blackness and sexual economic capital. I then did a part-time Art Foundation at AAL before gaining a bursary to complete my MA in Fine Art at Central Saint Martins.

How long have you been focused on film and technology? Was there ever a time when you were more involved in traditional mediums?

When I first started practising, I worked more with ceramics, sculpture, and sound. At the time, I was probing how these mediums can come together through spatial installations and how their arrangement influences our experience of meaning through space. This concern still very much rings true today. However, my interest in film and technology was born out of a heady mix of curiosity and necessity. In 2019, BLUE was invited to exhibit in Brussels by a collective called LEAVING LIVING DAKOTA. When developing this work, we became interested in how our digital lives were complicating traditional notions of selfhood as tied to the physical body. At the time, one of our members, Arna Beth, was the only person working in CGI, and the project load was too much for one person. I offered to learn 3D modelling and animation to aid in the production, and my interest grew from there really.

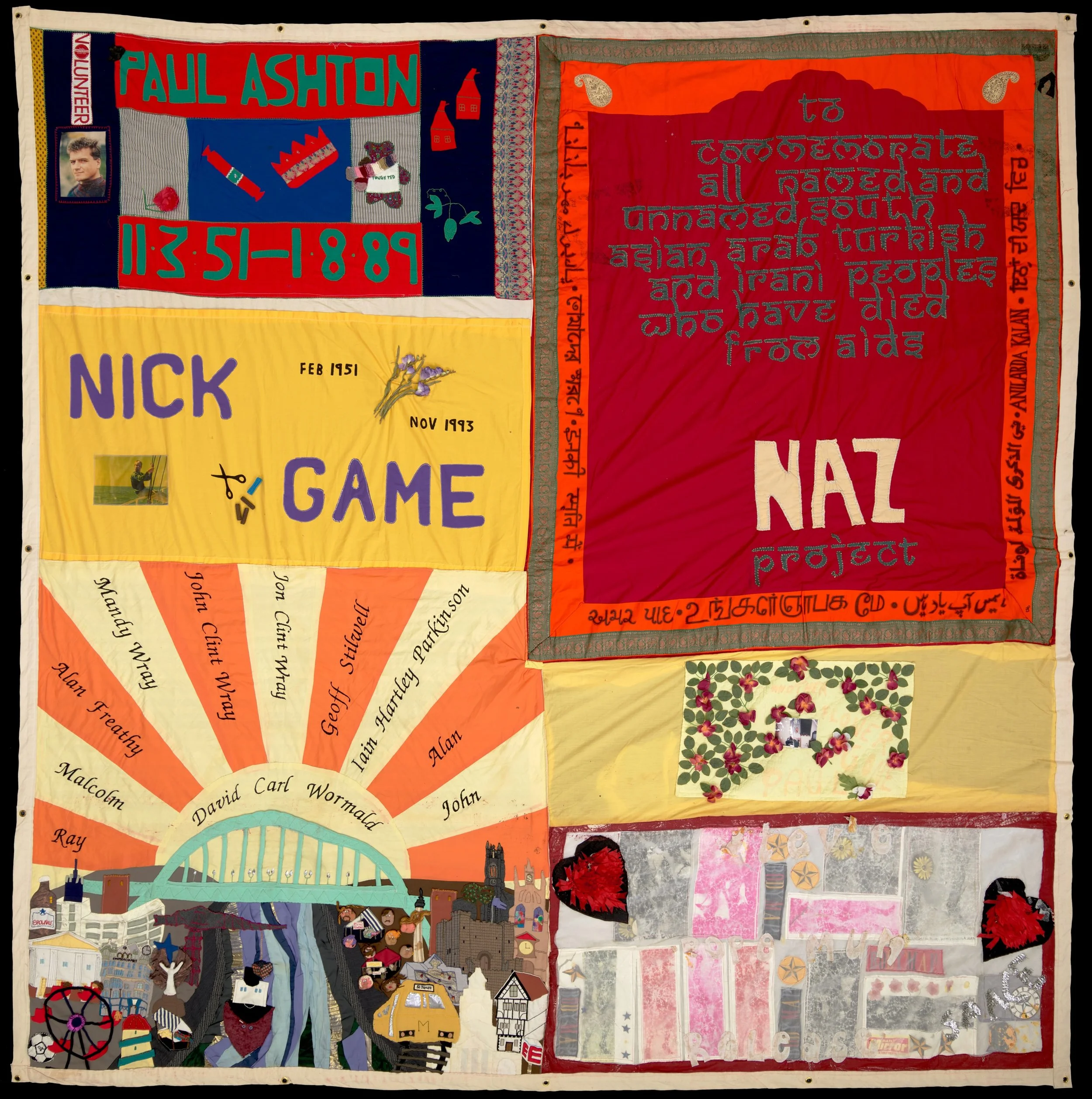

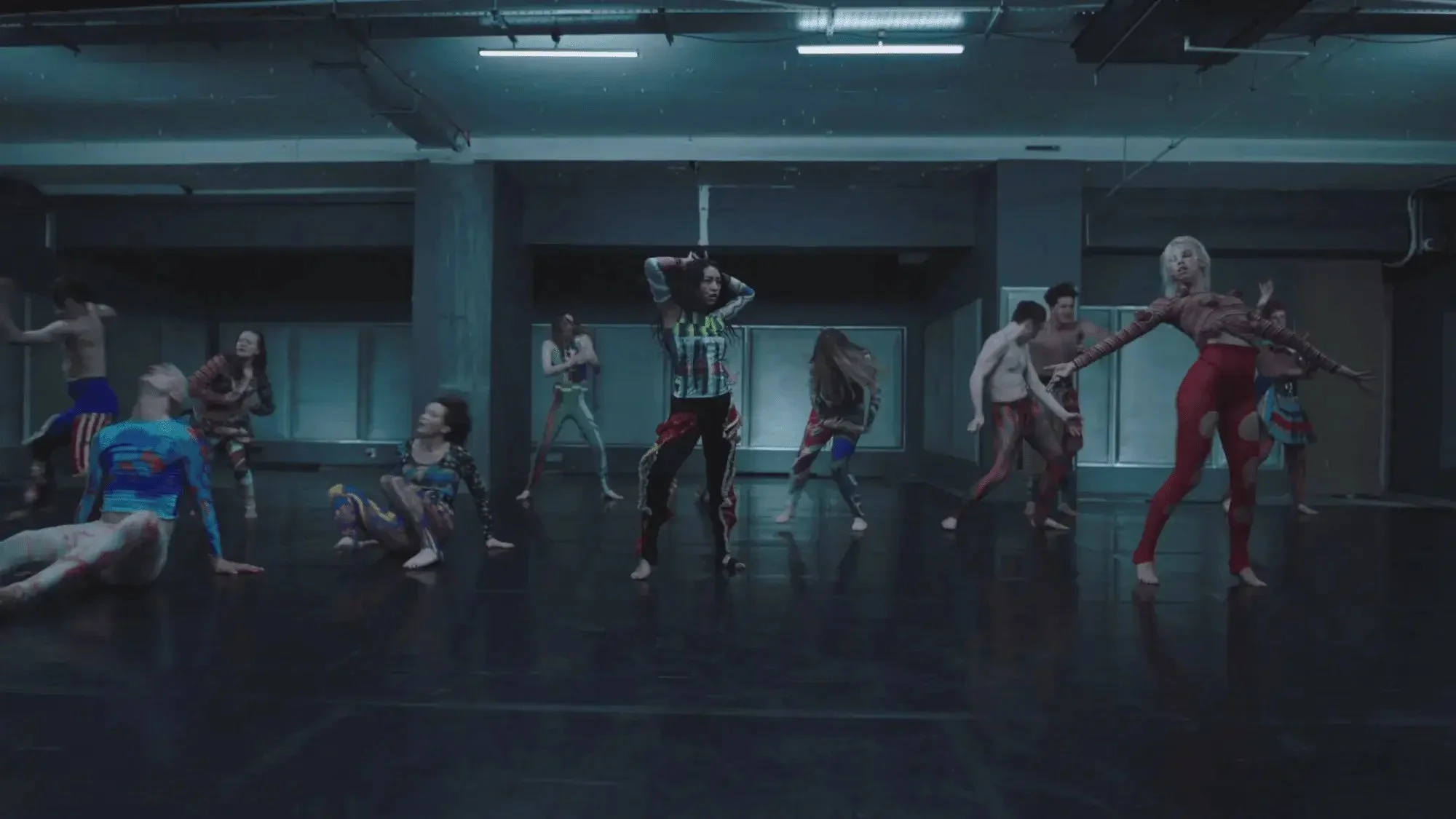

Dian Joy, Alexandria's Genesis, 2024. Installation view, arebyte Gallery, London. Image: Devika Bilimoria.

Tell us a bit about your current exhibition at arebyte Gallery, Alexandria’s Genesis? What was the initial inspiration?

The exhibition examines Alexandria’s Genesis, an internet myth that began as a piece of Daria fan fiction written in 1998 by Cameron Aubernon. I first encountered this myth through a viral post as a Black teenager spending far too much time on Tumblr in a predominantly white town. The post described an idealised genetic condition marked by pale skin, purple eyes, extended lifespan, immunity to disease, freedom from bodily waste, and unwanted hair growth. Though ideologically fraught, these markers of a gendered, racialised hierarchy were deeply alluring to a young person who felt at odds with their surroundings. Though I forgot about the post itself, these implicit notions of racial hierarchy were not peculiar, and this post became one item in a sea of media that formed the way I would relate to my own body as a young person. Last year, I happened to be reading up on old copypasta and stumbled across it again, and it was like a sudden rush of blood to the head. I knew I had to do some work about it. This time, however, I saw it in a different light—how it reflected societal anxieties about identity and desirability. My exhibition dissects this myth—not just as a curiosity—but as a lens into how the internet replicates and reconfigures hierarchies rooted in race and desire.

And as you were creating the exhibition works, did you know exactly how you wanted it to come together...or were some things surprising in the process?

Absolutely not. I would say I am more married to certain ideas and methodologies than I am to particular mediums and aesthetics. The process of my creating work is always very iterative and deeply involved. I get to points where I cannot see the wood for the trees. But eventually, you get to take a step back, and it is always surprising to see where you have arrived from where you thought you were going. I guess, when you prioritise research, in some ways, this does not lend itself to prescriptiveness. You are learning the terrain as you go and trying to come to some realisation about it. In the case of this show, that is where working with the original author of the myth became so crucial. I was struck by how much of the process of working with her revealed new layers of meaning that I could not anticipate if it were not for our collaboration.

Tell us about the experience of working with Cameron Aubernon, the writer who first conceived of the idea of Alexandria's Genesis (the fictional genetic mutation)?

Cameron has been very generous and very real with me throughout this process. The only reason I was able to connect with her, is because she had written a debunking post about Alexandria’s Genesis in 2011, where she revealed herself as its creator. In January, I made a LinkedIn account specifically to reach out and ask if she would be interested in collaborating on the project—and kudos to her for replying to an account with no connections or history, I would not have. From there, I interviewed her about the context in which she wrote the story and her experience of discovering that something she wrote as a teenager had spiralled into a viral conspiracy theory. We then worked together to design her virtual avatar and reconstruct the dorm room where she wrote the fan fiction. This collaboration culminated in a motion-captured interview that re-stages her reflections in the recreated dorm room, which was a really fun process. I think initially, Cameron was quite understandably wary of the work I was doing, which you can see within the exhibition itself. However, once it became clear that the work focused on deconstructing why certain pieces of media become viral and their cultural resonance—rather than treating the myth as an oddity—she was happy to be able to share her side of the story. In fact, we will be continuing our conversation during the finissage event at arebyte on 11th January, which will include a panel discussion and workshop curated by Alya Kanibelli of Reforum.

The exhibition definitely raises some scary ideas. What in your mind is the greatest warning here?

The image will not save you, the image will not keep you warm at night. Joking. But not really. I suppose the show asks viewers to think critically about the power of media and myths, especially as they circulate online. These myths do not arise in a vacuum; they inherit the biases and hierarchies of the societies that create them—the “warning” lying in how easily these narratives, once decontextualised, can shape our sense of self and our relationships with others.

Dian Joy, Alexandria's Genesis, 2024. Installation view, arebyte Gallery, London. Image: Devika Bilimoria.

What are the real-world implications of such internet myths?

In regards to how myths evolve on the internet, myths like Alexandria’s Genesis often proliferate within what is known as the vernacular web—online spaces that foster community through shared interests and niche cultures. While these spaces can be incredible for fostering communities, they often lack diverse engagement. This limited variety of perspectives can create echo chambers where ideas, unchecked by dissent, grow increasingly extreme or distorted. We have seen the dangers of this phenomenon in larger contexts, such as the role of social media in the Cambridge Analytica scandal or the rise of the alt-right. Myths like Alexandria’s Genesis may seem harmless by comparison, but they are part of the same continuum—reflecting and shaping our collective values in ways we do not always recognise.

How do you hope viewers respond to the exhibition?

I conduct my research to understand the world around me and how I fit within it. I make work to create spaces for the audience to locate themselves within the research. If this can happen, and we leap across the great chasm of meaning and meet halfway, that is all I can hope for.

Are there any other internet myths, or similar constructs, which you might hope to explore in your work in future (if you are able to say anything)?

The new frontiers of the self :)

Dian Joy, Alexandria's Genesis, 2024. Installation view, arebyte Gallery, London. Image: Devika Bilimoria.

The [Quick] #FLODown:

Any upcoming projects of note that you can discuss?

No comment (tee hee).

What have been the most rewarding moments of your career thus far?

Aside from this show, showing my first film at the BFI Cinematheque was crazy.

What’s the best advice you have ever received?

If you worry, you suffer twice.

Who are you outside of the ‘office’?

Baker, chess enthusiast.

What do you love about London?

The ghosts of my past injecting every corner of the city with a strange and pulsating significance. The ability to still become lost.

Alexandria’s Genesis by Dian Joy runs until 12 January 2025 at arebyte Gallery.

You can also attend the public programme curated by Reforum on Saturday 11 January, 3-6pm, for free – Through a dynamic mix of panel talk, roundtable, and workshop, the event unpacks digital folklore, exploring how myths mutate through memetics and copypasta. Moderated by Alya Kanibelli, digital culture experts and artists will interrogate post-digital identity formation and social contagion—revealing the blurred boundaries between fact, fiction, and collective imagination. Click here to book a free ticket.