In conversation with Enej Gala

“Ultimately it is only natural that the environments one crosses leave a mark in their practice.”

- Enej Gala

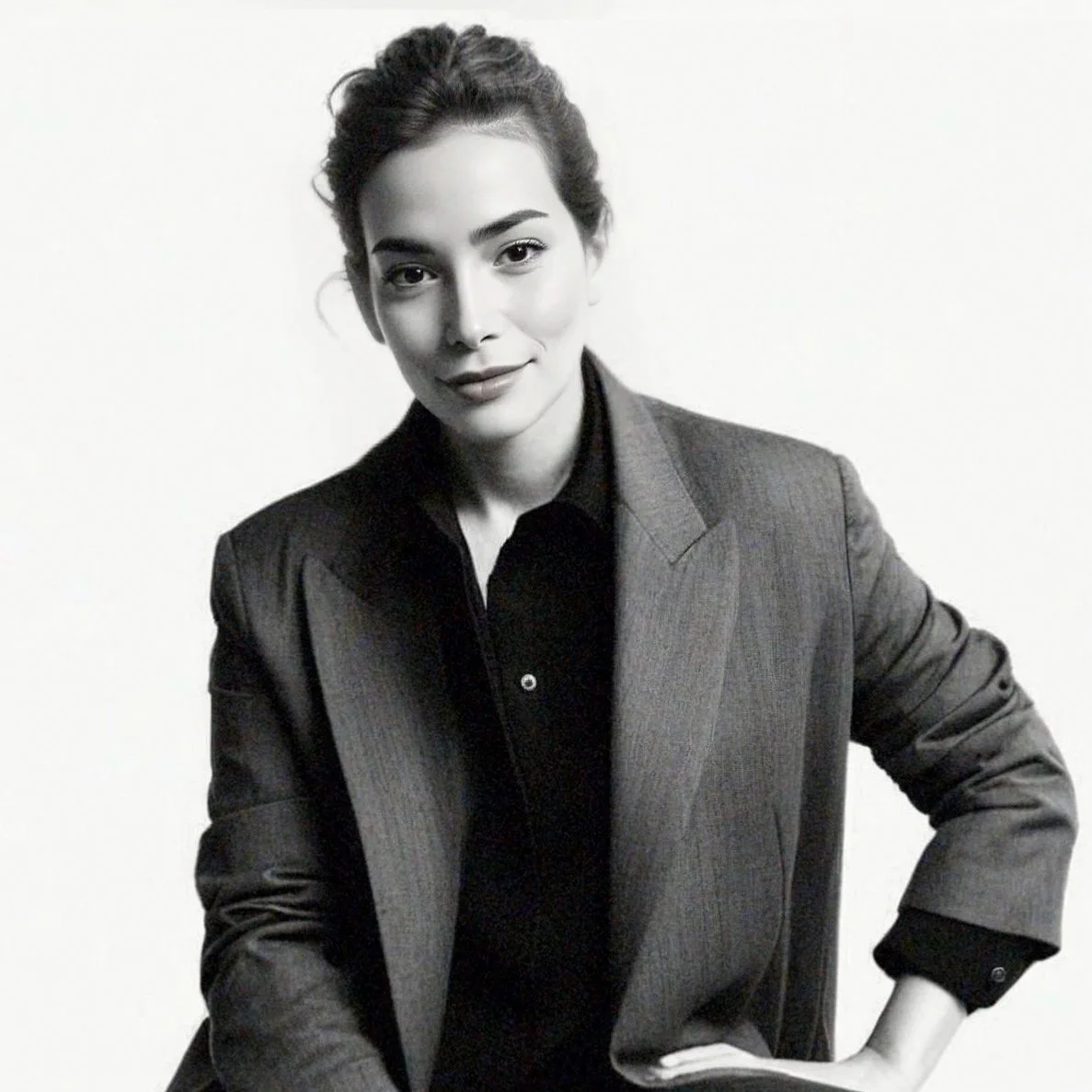

Enej Gala.

Enej Gala is an artist who splits his time primarily between London and his hometown of Nova Gorica, Slovenia. A graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice and the Royal Academy Schools (2023), Gala first gained our attention with Neighbour’s Harvest, an installation that cleverly combined puppetry and conceptual art, using sawdust from the RA workshops. This work reflects both his grandfather’s legacy in woodworking, the historical significance of his hometown and the deep rooted puppet tradition in Slovenia. His practice pushes the boundaries of art, craftsmanship, installation, and performance, often through collaboration and improvisation.

We had the privilege of visiting his Thames Side studio to explore his evolving practice and discuss upcoming projects, including his contributions to Nova Gorica’s role as European Capital of Culture. In 2025, Nova Gorica, together with the Italian city of Gorizia, will celebrate their shared history and culture, uniting across borders to showcase their intertwined identity.

You were born and raised in Slovenia, and your practice now spans multiple countries, including Venice and London. How have your cultural background and the diverse locations you’ve worked in shaped your approach to art? Do the histories and socio-political contexts of these places influence the themes you explore?

Living in a small town on the border between two countries with such different backgrounds, one rooted in Western capitalism the other in Eastern socialism, means being reminded of your specific background on a daily basis from day one. My work soon began to delve more intentionally into these complexities especially as I went to study abroad and got practically forced to face them. Ultimately it is only natural that the environments one crosses leave a mark in their practice. One soon discovers how peculiar histories intertwine and reflect even over great distances.

Who or what first introduced you to the world of art? Were there any early experiences or individuals who specifically influenced your decision to pursue a career in the arts?

I could blame a few people, but probably the very first was my mother, who, from an early age, regularly took me to puppet shows at the local theatre. She and my grandparents came from a small town, Solkan, known for its long woodworking tradition, a memory my grandfather worked hard to preserve. Interestingly, it’s also the birthplace of Slovenia's first puppeteer Milan Klemenčič. On my father’s side, my other grandfather did woodcarving in his later years and even held some shows. Though I never met him, it seems his work was deeply influenced by the many harsh experiences he had as a partisan doctor. I've always been drawn to working with hands, experimenting with different materials.

I spent some years in a local theatre group led by Emil Aberšek, but soon found out I like the craft more than the stage. Some teachers and friends encouraged me throughout my schooling, but I don’t think there was ever a dramatic 'eureka' moment where I decided this was my path. It felt more gradual and instinctive—creating things to see what was possible, slipping deep into curious loopholes that I still rummage around in.

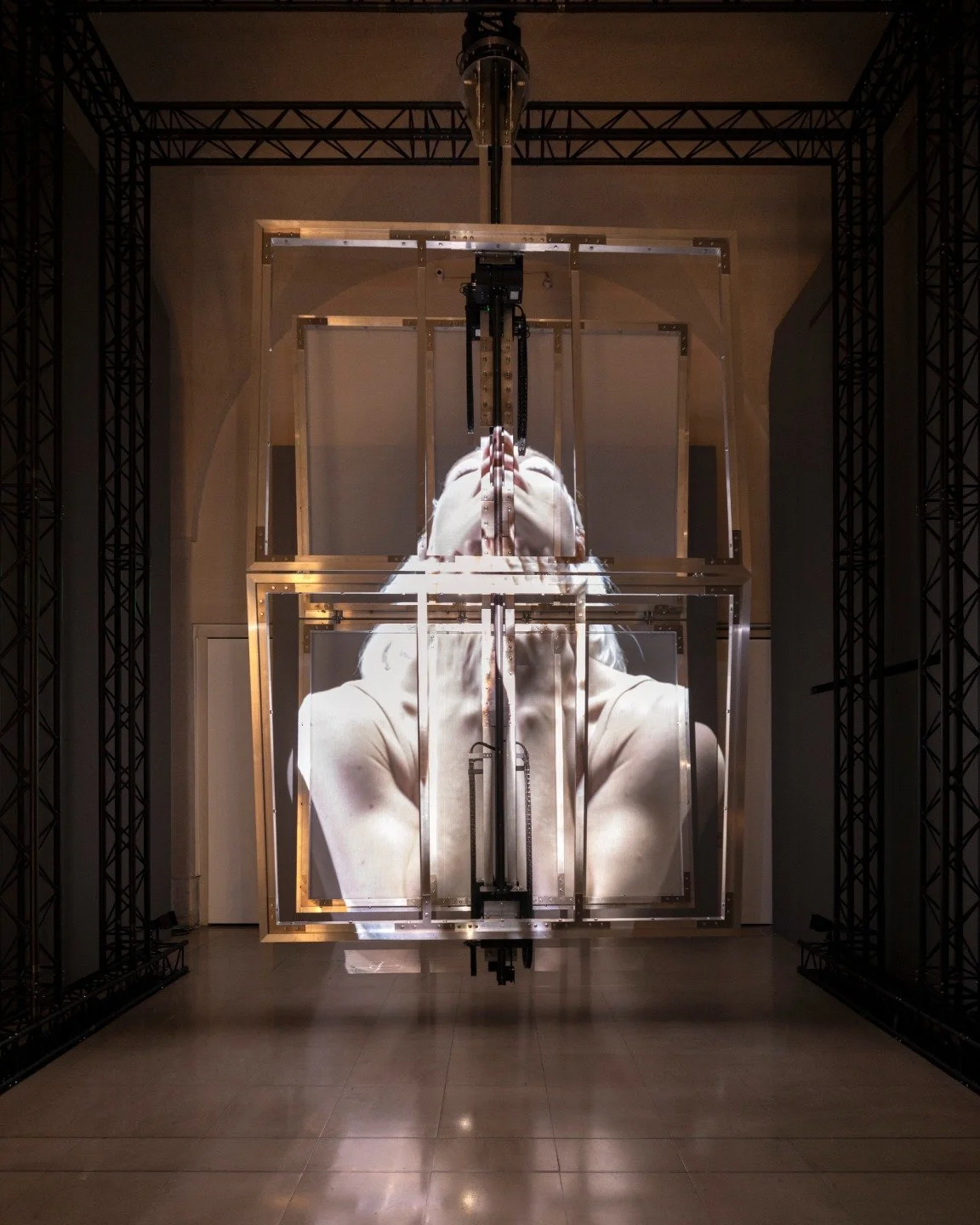

Falsetto, 2024, exhibition view at Toast project space, Manifattura Tabacchi, Florence (IT), photo by Leonardo Morfini.

The use of puppetry is prevalent in your work, often shifting from performance to something more abstract or symbolic. Can you explain how puppets in your art transcend their typical function as mere objects of manipulation and take on a life of their own within your installations?

I made a pact with puppets to help me convey and interact with serious conceptualism from its diametrically opposed angle. Transcending their role as mere instruments, they can address even the most painful or intellectually rigorous experiences with just the right mix of earnestness and humor. Emerging from virtually every tradition, spanning from sacred to profane, puppets have served as basic tools to externalize and gain awareness of ourselves, our social norms, and our most common or absurd behaviors. Even when stripped of all connotation, iconography, or function, I see them as intrinsic tricksters, with a couple of great paradoxes up their sleeves: the more one follows them, the more they seem to follow, and their magic tends to increase, even when all the tricks are revealed. Like some ultimate manipulators, they use others' power to gain theirs. Dissecting their physical, conceptual, and narrative potential, I constantly find myself amused by the endless new categories of their possible freedoms.

You’ve described your work as an ongoing dialogue with the material itself. How do you view the physical act of creating—whether carving, moulding, or constructing—as part of the larger conceptual conversation you’re having with your audience?

Materials and methods within the work are the converters of ideas into palpable realities. By observing how something is made, one gains a broader perspective and inevitably a deeper understanding occurs, as each material adds a layer to the conversation a work opens. Making is an integral part of the work, which I enjoy and value a lot. Especially nowadays with how overwhelming multitasking can be, I can never emphasise enough how important it is to focus, and take time for each specific technique that different materials dictate. For example, to make a single Wheelbarrow I spend approximately one week sewing by hand, which is preferably done in winter as the fur keeps me warm and the humidity makes it difficult for other materials to dry. The process as such dictates terms and becomes crucial to understand certain conceptual twists within specific works.

Saving chewing gums from mammoth's hair, 2023, exhibition view at TJ Boulting, London (UK) photo by Tom Carter.

Many of your works explore the relationship between objects and their inherent meaning, often blurring the lines between the material and the symbolic. How do you decide which materials or forms best convey the conceptual themes in your work?

The work usually reveals itself as the single common denominator of a material, a form, and a concept. The forms and materials are the carriers of certain themes and specific concepts because of their intrinsic or attributed values. I merely observe the materiality and extrapolate a function that subverts or transcends its value. If the visual potential gets maximised while an idea is boiled down to its basic ingredients, the transformation process occurs at its best.

Your work often focuses on ‘otherness’ and explores the experience of being an outsider. How do you approach this theme in your practice, and what does it represent to you personally?

I always found it fascinating, how only the ones categorised as others, can truly know what it means to be the other, but at the same time they do not know that they are others, until a dominant group forms their otherness through a discursive process. Something analogous to when the oppressed need to learn their oppressor's language and rules to be able to address the problem of being oppressed. Puppetry always dealt with the other as the puppet itself is a smaller, bigger, lesser or mightier other to its creator/manipulator as well as the beholder. Having spent most of my life living on a border between two cities, two states, two, or three ethnolinguistic groups and often travelling to different countries, one develops a different sense of belonging. When I say back home, I must always specify which home I mean, even to my closest friends. So the otherness with its many faces is always present and urges me to be constantly addressed.

Acquaintance, 14 string marionette, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

You tend to challenge traditional notions of what art is and how it should be consumed. What are your views on the current state of the art world? Are there aspects you believe are holding art back, or elements you’d like to see more of?

I don't like art being consumed. It is an experience one can hold on to and return to when needed. The main problem is still wealth distribution and the high-end, rat-race capitalist model that the art world can't really dissociate from. Art has many socio-political functions, which seem to be the first to be exploited in such a system. Everything is propaganda, but there is a big difference between what we are propagating for and how consciously unconscious the whole deal is. I'd definitely like to see more funded projects with proper purposes, acknowledging the many valid functions art has, other than money or consciousness-laundering facilities it seems to prevalently provide.

In a world increasingly driven by spectacle, where does your art fit? What do you believe the role of art should be in addressing or challenging the status quo, especially during times of social and political upheaval?

Spectacle has its role but must not become the purpose. To be fair I think most interesting things usually happen away from it. In times of social and political upheaval, art can definitely serve as an act of resistance. We can see this happening in virtually any form starting from something so small and futile as a meme. How effective it is in different circumstances is another question. Simply put, art is a necessary act for when one does not necessarily need to act. It confronts us with the cracks, bruises and paradoxes of the real. When facts serve us the utmost brutality, one needs a great deal of imagination to form a viable alternative; art is a way to train it.

If you haven’t got it in your head you’ve got it in your heals, 2022, exhibition view at Aplusa Gallery, Venice (IT), photo Clelia Cadamuro.

How do you view the relationship between artist and audience in your work? Is it important for you to evoke a specific response, or do you prefer that your art leaves room for personal interpretation?

When I plan a show, I consider the audience as this necessary encounter I need to be extra aware of. A show is a kind of trap for the brain to stumble upon and work their way out. This is not always the case in the studio though, where experimentation is practised and invention occurs, some works often never leave or encounter anyone else than their maker. Personal interpretation is unavoidable. To a degree one can predict some reactions, but there is always the possibility the audience will misunderstand or reinterpret things even when the intention of the artist is seemingly clear, yet this is also what makes things more interesting and challenging.

How do you envision your practice evolving in 2025? Any upcoming projects of note that you can discuss?

It looks like I will be traveling some more, but actually fairly near my hometown, Nova Gorica, where I am currently involved in two separate projects for GO!25: one as a scenographer in a puppet show called Gora with director Giulio Settimo, a co-production between the Puppetry Theatre of Ljubljana and the Theatre Rossetti of Trieste, and another where I will be working with two of my long-time collaborators, curator Nataša Kovšca and all-around musician Tomi Novak, on a sound installation in a tunnel near the border between Nova Gorica and Gorizia.

In Bologna, I will have two collective shows—one with the amazing curator Enrico Camprini at the historical Galleria De' Foscherari, and another a bit on the outskirts, in the 17th-century Villa Davia situated at Borgo di Colle Ameno, Sasso Marconi, a project under the patronage of the Fondazione Guglielmo Marconi and Comune di Bologna, curated as a collaboration between two inventive visual artists, Moe Yoshida and Iside Calcagnile, and the art space Adiacenze. This show will revolve around Marconi's genius as a peculiar figure of influence in radio wave-based telecommunication. There is always something cooking with the expansive Venice collective Fondazione Malutta, I am a part of. So, this year, I will probably be spending most of my time between these cities, but with some luck, you might also find me at Thames-side Studios in London.

Rockers, 2024, a work in collaboration with Moe Yoshida, exhibition view at Dolomiti Contemporanee, Nuovo Spazio di Casso (IT) photo by Teresa De Toni.

The [Quick] #FLODown

Best life advice?

Train your gratitude.

Last song you listened to?

Çadirimin Üstüne by emerging Slovenian band Grunt.

Last book you read?

Bread, Dust by Marko Sosič.

Can't live without…?

Laughter.

What would be your dream project?

A longer video production involving puppetry and improvised music. Lately, I have been developing more video work which I really enjoy and would love to do more.

Website: enejgala.com

Instagram: @enejgala

Facebook: Enej Gala

LinkedIn: Enej Gala