In conversation with Asim Waqif

“I'm looking more at designing experiences for viewers rather than just limiting myself to the visual aspect.”

- Asim Waqif

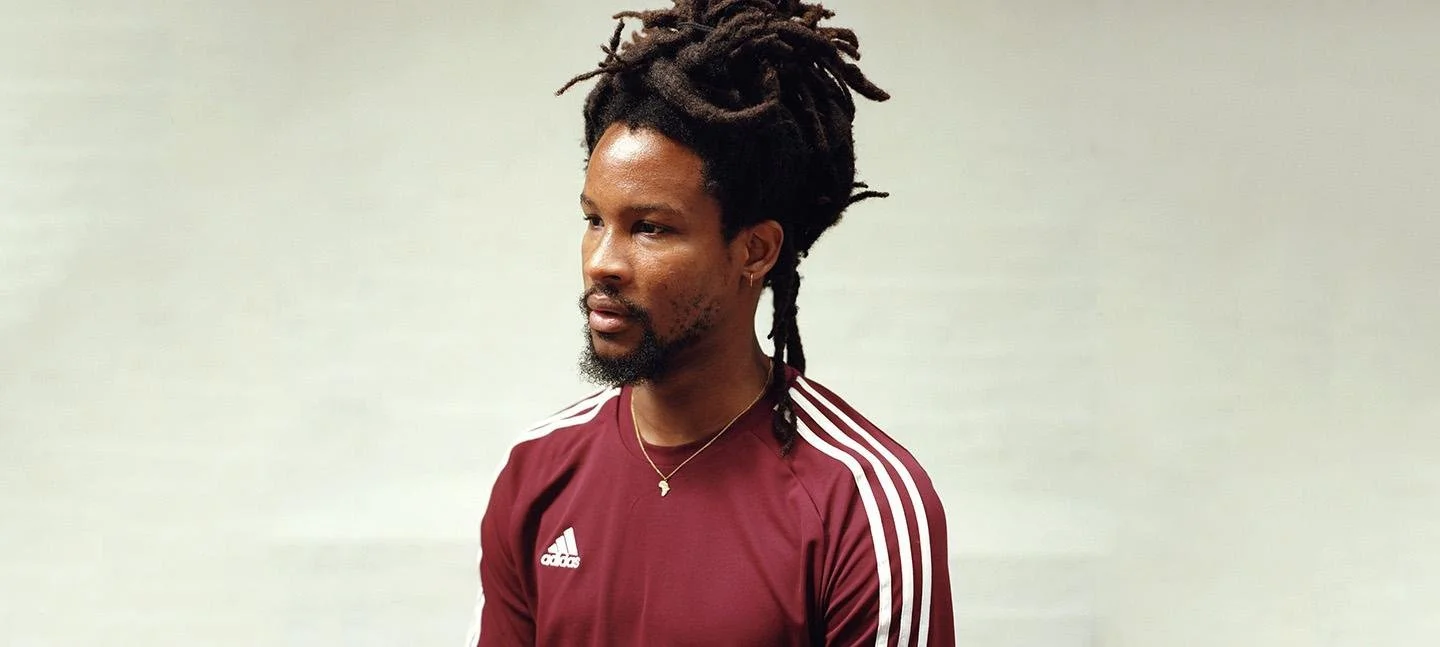

Image: Asim Waqif वेणु [Venu]. Courtesy of the artist. Photo © Jo Underhill.

Asim Waqif is a Delhi-based artist, whose recent projects have focused themselves at the intersections of architecture, art, design, and spatiality. His work invariably references urban design and the politics of public space. Asim studied at the School of Planning and Architecture in Delhi, after which he worked as an apprentice in a carpentry workshop. Following his time as an apprentice, he began working as an art director for film and television. Subsequently, he embarked on creating independent videos and documentaries.

From the 20 July - 22 October 2023, The Hayward Gallery Terrace is presenting an installation from Asim titled वेणु [Venu]. His bamboo installation is the third Bagri Foundation Commission. The piece deals with themes of urban space, ecology, community, and organic systems.

The bamboo for Asim’s installation at Hayward was donated by the Misty Mountain Experience in Peermade, Idukki, Kerala, India, and the commission has been created in collaboration with architect Shantanu Heisnam. Please read more about Asim’s work here or on the Southbank Centre Website.

How did your journey into art begin? What was that trajectory like?

Well, actually, I never thought I'd become an artist. I'm still a bit reluctant introducing myself as an artist. I studied architecture and was doing set design and exhibition design after I graduated. I was not so interested in setting up an architecture office. But I like to work on-site in set design and exhibition design. Things were quite fluid at times and I really enjoy that process. One of my friends used to work in a nonprofit arts organization here in Delhi called Khoj. I used to just go for the openings because my friend was there. But something must have clicked because then I set up a meeting with the head of the organisation and proposed an idea to her. She was very supportive and that's how I did my first art project.

Coming from a design background, it was a really rewarding experience for me because I could push ideas as far as I wanted or stop when I wanted. And then, in fact, Pooja Sood — who's the director of Khoj — pushed me to do another project in 2008. In 2009 and 2010, I did a few group shows, but I thought people were not really taking me seriously, like ‘There's this architect who's dabbling in art once in a while.’ So, from 2010, I made a strategic decision to start introducing myself as an artist, and that really worked wonders in terms of the opportunities that opened up for me. So, that's how I got into practicing art.

How would you describe your artistic style? What would you say the most recognisable characteristics of your work are?

Usually, I like to leave definitions of my work to other people rather than describing it myself. But what I've become really keen to work on, especially when I'm working on large-scale projects, is I want to try and see if the entire fabrication team can be part of the creative process rather than this kind of top-down approach, that is a common thing in most creative fields today, whether you look at architecture or design or even art; where the person on the top decides what has to be done and the rest of the people are just executing it.

I find that the process of making things can be a very fruitful space for creativity. I mean, of course, there is an overall concept where I am controlling things in some way, but what I'm trying to control more are systems or layouts rather than the details of how each and everything is executed. I try to see if I can find a particular skill-set that I need and then find resources that are relevant to that skill-set and create a space where that kind of work can really fructify and challenge its own kind of process in some way.

At the same time, quite often in my projects, there are many skill sets that are mixed with each other. So I also want to try and see if people can learn from each other while they're working together so that there can be some cross-training, even interference. I get really excited when something I never imagined gets built during the process of fabrication.

Image: The Bagri Foundation Commission_ Asim Waqif, वेणु [Venu], 2023. Courtesy of the artist. Photo © Jo Underhill.

With such a global reach to your art, what messages and themes do you try to communicate in your work, and how has this evolved over the years?

There are to some extent some ideas of sustainability, ideas of reuse, and upcycling that I'm very keen to kind of explore. But also now, more and more, I'm really interested in actually trying to subvert the museum experience in some way. Actually, I find going to museums to be quite a boring experience. This seems to be a barrier between the viewer and the artwork, and even if it's something made out of stainless steel, some material that will not really get tarnished if somebody touches it. But you are never allowed to touch or feel an artwork. I find although — I guess technically I'm a visual artist — but actually, I'm looking more at designing experiences for viewers rather than just limiting myself to the visual aspect.

At the same time, I feel — because I've done work in the nonprofit space as well in terms of activism — art actually gives a really interesting opportunity to tackle a subject without being very didactic or without taking a very definite side. While activism is usually quite confrontational or it tries to show some kind of utopic or extreme way of doing things. So, I consciously try not to have a very direct or obvious message. Instead, there are certain hints that are available to the viewer. I try to create a situation where people forget that they are in a very formal art appreciation space by using different game mechanisms — humor, musical instruments, interactive systems — and then the viewer kind of enters this almost juvenile, carefree kind of space. And that's a really powerful time to affect somebody's thinking in subtle ways. What I found most successful is if the question becomes evident, but the answer is not easily available. So then the viewer is forced to think of the answer himself or herself. That kind of introspective question and answer has more impact on one's thought process. Rather than having a very obvious answer because then people just tend to process that and move on, rather than something lingering in their mind.

How does your work connect with the natural environment and incorporate ecological themes in presentation and in the making process?

The thing is that today, although, we are exploiting more and more natural resources, we process them to a higher degree before we use the end result. As an economic model, we have quite an exploitative relationship with natural resources. And not only is it exploitative, it is also kind of all-consuming. Also, we have a lot of planned obsolescence, which is a really important part of the design industry, which basically makes things defunct before their life is over so that people have the opportunity to buy more stuff. This has created a situation where we're just trashing more and more stuff.

Even in the post-industrial West, I found that, more often than not, the waste disposal mechanisms are more to take care of the guilt of consumption, not so much to actually do something good with the material. So the user puts the right kind of trash in the right coloured bin and feels he's fulfilled his responsibility and feels entitled to go and consume more. But more often than not, municipalities and governments are not really doing a very good job of recycling or up-cycling this waste. So it's a mix of things. I wouldn't say that I'm working only with natural materials, but I do like some aspects of working with natural materials. I've also done a lot of work with discarded material.

Image: Details of Asim Waqif, Improvise, fifth Kochi-Muziris Biennale, 2022 © the artist.

Bamboo is something which has gotten stuck to me in some way. In fact, I did my first couple of art projects with bamboo, and then everybody started calling me a bamboo artist, and I didn't like that at all. So I actually moved away from bamboo, and I did work with many other materials for many years. But in 2019, I got an opportunity to do a project in Kolkata, which was a pavilion for a large religious festival called Durga Puja. Usually, these pavilions are made out of bamboo, so bamboo seemed like the ideal material for that project. In the pavilions, traditionally, although bamboo is used to make the structure, often the bamboo is covered up with decoration, with fabric, paper, or other materials. But, I wanted to use the raw material itself as the aesthetic element. So that's when I got back into bamboo. Now everybody is calling me a bamboo artist again, and I'm not so happy about it. But I still like working with it; it’s really versatile.

Also, I think in terms of design and sustainability, it is a material and it's a craft form that is going through crazy transformation. At one level, we have the high-end design and sustainability world adopting bamboo as this wonder material. Which, also I'm not totally happy about, in some way because it's not that bamboo is completely sustainable. There are many places I've seen where bamboo has become an invasive species, especially in Europe. But it's got this kind of [air] as though everything about it is sustainable; like just the fact that one uses bamboo makes something sustainable. That's not really true because a lot of the way the design industry uses bamboo is actually in composite panels like plywood made out of bamboo, which have adhesive and different chemicals in it. Even the people who are using whole bamboo, are using whole bamboo as though it were a pipe-section. Then the pipe sections are joined with metal joinery or wood joinery to make trusses.

The other really different thing that's happening with bamboo is that all the people who've lived and worked with bamboo for generations and generations, for them it is a very important step to move away from it. Aspiration, development goals, and agenda of modernising are pushing people away from the use of bamboo to more industrial materials. In fact, building policy is very heavily lobbied by the steel and cement industry. So, for example, in India right now the government has this scheme for giving money to poorer people to make their own houses. You will only get the grant to make a brick, cement, or concrete house. Bamboo is not a legal material to use in this scheme. If you're making a bamboo house, you won't get the grant. I find that these are really diametrically opposite situations of bamboo. This is something that I want to try and make meet in some way, so that high-end design is able to play with the experience of generations of working. All the while, these people who have been working for generations and feel that they should move away from bamboo realise that there is a market for really high-end bamboo products. Somehow they can meet and work together.

Image: Asim Waqif वेणु [Venu]. Courtesy of the artist. Photo © Jo Underhill.

Your installation, वेणु [Venu], will be in place at Southbank Centre on the Hayward Gallery Terrace until mid-October. Can you tell us how this particular installation came to fruition?

So the project I did in Kolkata — the religious pavilion — was a really amazing process. What came out of that project was very well appreciated. Because of that, Kochi Biennale, when they invited me to do a project for the last edition, was really keen that I use bamboo. I made an installation there in Kochi for the Biennial. It just so happened that a curator from Hayward, Yung Ma, was visiting Kochi a little later on after the opening. He contacted me and asked me whether I could make it for Hayward. The timeline was really short… I think it was like 4 or 5 months. Also, I knew I would be really busy this summer because I had a project in Pittsburgh — I just opened a solo show there before Hayward. At first, I told him, ‘No, it's not possible.’ But he insisted and also I thought, ‘It's not that you get an opportunity to work with Hayward again and again, so I should try and see if I can make it work.’ So, yeah, that's how this project happened.

While I was researching for Kochi, I chanced upon — through some friends of friends — somebody who had a 3000-acre plantation. Part of it is tea, but a lot of it is just forest and there's some bamboo growing there. We partnered with this tea estate, Misty Mountain Experience, and they gave us the bamboo for free for both Kochi, as well as Hayward. That was really good because then I had control over the harvesting process and then the sizing and craft of making strips out of the bamboo. Before shipping it to London, we treated it with this mineral called boric-borax, which prevents borer insects, but is considered safe for humans. Later, we found that it's also a fire retardant, which Hayward was very happy about. So, all of this process was done in the south of India and then the bamboo was shipped over to London.

What was the project that you were working on in Pittsburgh?

It's on for a year, the exhibition in Pittsburgh. The Pittsburgh project was very different from the Hayward Gallery Project in the sense Hayward had seen a previous project of mine and they were interested in me making something similar to that at Hayward. But, at Mattress Factory, once they chose me to do a show they were like, ‘Okay, so what do you want to do?’ They had no agenda. I mean, of course, there was a space constraint in some way, [or] a designated space. Also, there was some budget, and actually, I even asked them, ‘What is the budget?’ They said, ‘Don't worry about the budget. You just figure out what you want to do and we'll try and do it.’ So that was a very open-ended kind of a project, much more of an experiment in terms of its making. While for the Hayward Gallery, the language and the material were already pre-decided. It was about how one can make it happen in a place that does not have the skill set to work with bamboo.

Are there any noteworthy upcoming projects you can discuss at this time that you’re particularly excited about?

Yeah, I'm actually participating in the Chicago Architecture Biennial, which is open on the 1st of November. So, while I was in Pittsburgh, I visited Chicago, just to see the place and do some research on materials. Then, I made a proposal and we're going to execute it in October.

What has been the most rewarding moment of your artistic journey thus far?

In some ways, I feel I've had the opportunity to explore ideas that I think other creative industries do not have much space for. Unfortunately, today, design is dominated by profit to a very large extent. So it doesn't matter whether a design is good or not. What matters is whether it's marketable or not. And, I didn't know that about art when I started working as an artist, but I somehow have had a chance to show creative potential for many ideas of sustainability and of economy.

The other aspect, which I briefly mentioned, is I've started on a collaborative way of working, which requires very good teamwork. It also requires a lot of trust. In fact, most fabricators now feel that it's not their job to be creative. They just want to follow instructions. Especially in a museum environment, where the installation staff is trained not to make any creative decisions. They're told to follow very specific instructions and not do anything out of that. This is a shame because, actually, most people who are on installation teams in museums have studied art and have a very good understanding of creativity. So I really enjoy that: working in a collaborative space with people with different skill sets. It takes time. It takes trust. Also, ego can sometimes play a role — ego and insecurity — which I think artists have too much of — both insecurity and ego.

वेणु [Venu] will be on at The Hayward Gallery Terrace from 20 July 20 - 22 October 2023.

For further information on Asim Waqif and his creative journey:

Website: asimwaqif.com

Instagram: @asimwaqif

Word by Sara Bellan

This interview has been edited for grammar and clarity. If you would like to read the unedited transcript, please email hello@flolondon.co.uk.