The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998, Barbican Art Gallery review

Having just spoken this week to a friend about the shame of being unfamiliar with artists in Asia despite growing up in Southeast Asia I was delighted with the opportunity to see this exhibition featuring 150 works of art from 30 artists capturing life during this era of social upheaval, economic instability and rapid urbanisation.

The exhibition is bookended by two pivotal socio-political occurrences in India’s history – the declaration of “the State of Emergency by Indira Gandhi in 1975” and “the Pokhran Nuclear Tests in 1998” giving birth to the world’s first exhibition to explore and chart two decades of significant cultural and political change in India. The works encompass painting, sculpture, photography, installation and film. This landmark group show reflects a mixture of daily, tortured and intimate moments of life during this time.

Nilima Sheikh’s Shamiana. The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998. Installation view. Barbican Art Gallery. 5 October 2024 – 5 January 2025 © Eva Herzog Studio / Barbican Art Gallery.

The exhibition is named after essays by Sudipta Kaviraj, which discusses the process of instituting democracy and modernity in post-colonial India. The essays position Indian politics within the political philosophy of the West and alongside the perspectives of Indian history and indigenous political thought.

With all the works combined you have some works presenting social observation with individual expression while others simply captured shared experiences and private moments to make work about friendship, love, desire, family, religion, violence, caste and community. The exhibition is in roughly chronological order and shaped into four axes: the rise of communal violence; gender and sexuality; urbanisation and shifting class structures; and a growing connection with Indigenism.

Navjot Altaf (b. 1949) Emergency Poster, 1976, ink on paper, Collection of the artist. Photo by Natascha Milsom.

The first room has two Emergency Posters (1976) by Navjot Altaf who as a member of the left-wing Progressive Youth Movement (PROYOM) made these drawings in preparation for screen printed posters to be used for marches, sit-ins, rallies and activists’ meetings protesting government corruption during this period of suspended democracy.

Following the Emergency artistic practices the artists committed themselves to representing everyday life of working-class figures. Examples of Sudhir Patwardhan’s figurative style are on display in figurative expressionist drawings on one hand and large complex oil paintings of town and cityscapes on the other. They express empathy for their subject’s resilience, internal strength alongside their vulnerability.

The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998. Gieve Patel, Off Lamington Road, 1982-86. Collection: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi. © Gieve Patel. Courtesy Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke and Kiran Nadar Museum of Art.

An epic painting of Gieve Patel’s Off Lamington Road (1982-86), is characteristic of his style depicting people on the fringes of society and this painting is no exception with two bandaged leprous children begging for alms and a woman lying in the foreground naked and bleeding, yet this is side by side with groups of men and women talking and young people dancing dressed in colourful clothes. Patel appears to keep a critical eye on society and its darker aspects.

Sunil Gupta (b. 1953) presents Exiles, a series of colour photographs featuring staged images set against well-known landmarks in New Delhi, such as India Gate, Humayun’s Tomb, and Connaught Place, as well as lesser-known cruising spots. The series captures the lives of gay men in Delhi at a time when homosexuality was still a criminal offence in India. The law was enacted in 1861 and was only repealed in 2018. The images are accompanied by excerpts of conversations with his subjects all voluntarily offered. He had the consent of his subjects with the understanding that the images would never be shown at the time in India. Continuing to explore gender and sexuality are the works of Bhupen Khakhar, an accountant by training and a self-taught artist began to address his homosexuality which he had struggled with until then. His painting Two Men in Benares (1982), is a bold piece of art for its time.

The next space moves to the topic of equality for women in a series of 19 black and white photographs by Sheba Chhachhi (b. 1958) who became involved in the women’s movement when she returned to her hometown of Delhi in 1980. It follows seven female activists during a wave of protests against dowry-related violence and Chhachhi photographed her fellow campaigners. The staged portraits of the women she came to know for a decade are powerful giving them agency and control over their own representation in what can be seen as a collaborative work with her sitters. Each woman chose and co-developed her mise-en-scène, to ‘tell her story’, and perform herself, as well as review and retake till a final image was reached hence the usual asymmetry between the photographer and the photographed is somewhat addressed.

With this collection of photographs is also a series of 12 smaller narrative paintings by Nilima Sheikh of a girl she knew titled When Champa Grew Up. Champa was married off while a child then subjected to abuse in her new home and eventually killed within a year of her marriage by her in laws and husband in a dowry related murder. These paintings on paper are not macabre in the slightest and move gently forward from her idealistic life as a young girl which seems a gentler way of reflecting this fragile story.

Sheba Chhachhi (b.1958), selection of black & white photographs 1980-1991. Photo by Natascha Milsom.

There is a collection of beautiful small-scale and intricately detailed sculptural works by Meera Mukherjee (1923-1998) who studied metal casting techniques with artisans in West Bengal and Nepal. The sculptures present figures from everyday village life: labouring artisans, and students in mass protest and religious devotees.

Savindra Sawarkar (b.1961) exposes the pervasive oppression and discrimination in Indian society based on class and caste and moves away from the bourgeois centred Indian art world by giving visibility to the persecution of Dalits categorised as “untouchable”. Under medieval Peshwa rule Dalits had to collect their spit in a pot and sweep away their footprints. Hence the visual markers of the Dalit experience became the “matka (pot) and ‘jihaadu” (broom). His works with bold, dark inky lines etched repetitively form shadows which reflect their plight.

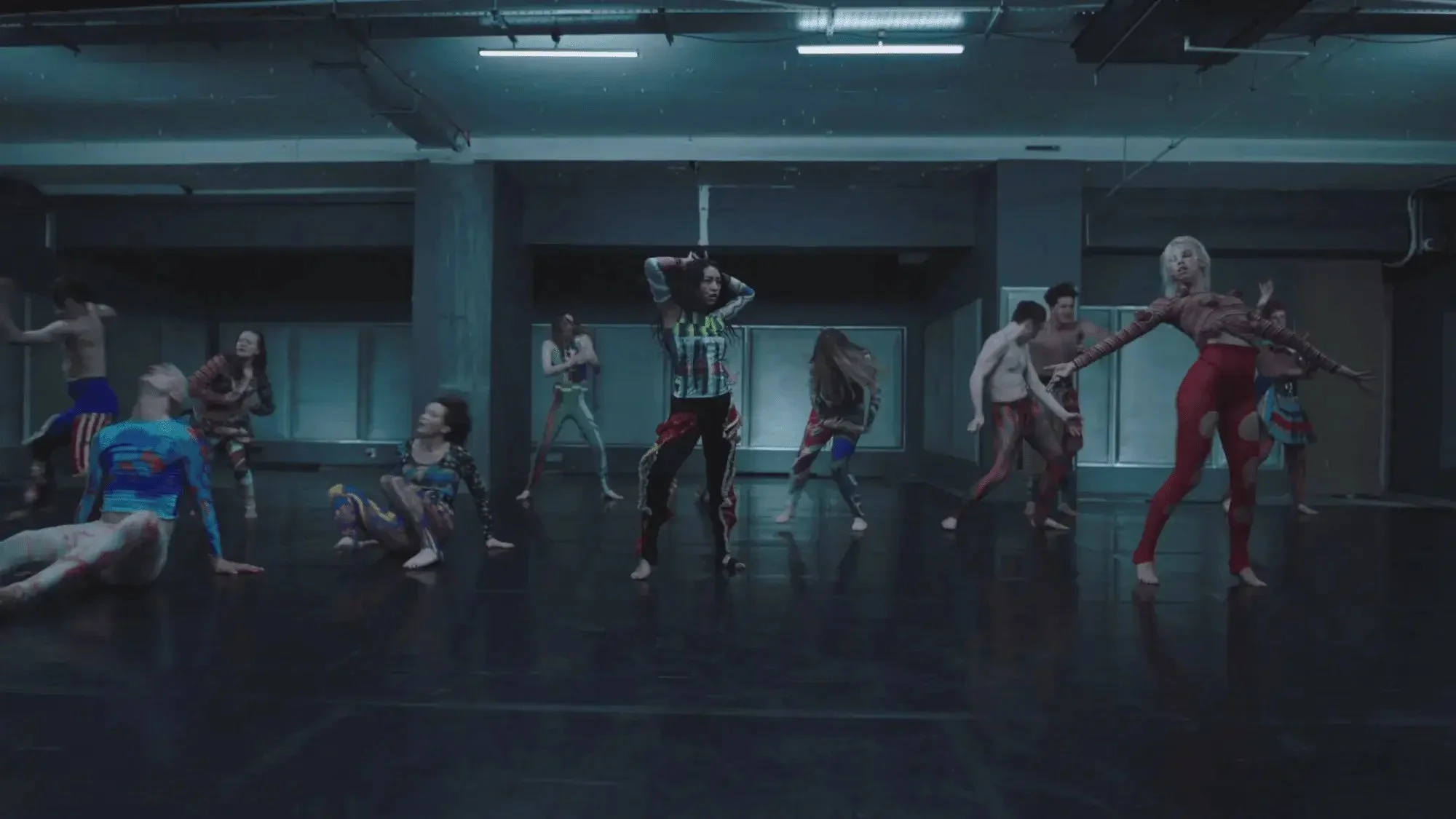

The lower level reflects the more installation-based approach which became popular with many artists in the 1990. There are some impactful large-scale installations, mixed media and sculptural pieces:

Nilima Sheikh’s Shamiana forms a colourful centrepiece which can be seen from most parts of the exhibition with a canopy painted in acrylic, and double-sided painted scrolls, or “kanats” (side screens). This work centres on the journeys taken by women for devotion, love and celebration in the face of hardship and allows visitors to move around and cocoon within this uplifting installation.

The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975 - 1998. Vivan Sundaram, House, 1994, from the series Shelter, 1994-99. Photo by Gireesh G.V. Photo courtesy The Estate of Vivan Sundaram.

Vivan Sundaram’s House (1994), from the series Shelter reflects the changing political landscape and tensions in India at the time. Its surface carries embossed emblems of tools of labour and the outer walls exhibit marks of brutality: scattered limbs, jagged outlines of weapons and closed windows

N. N. Rimzon The Tools (1993), is a figure standing in a state of meditation encircled by iron tools and broken parts of agricultural equipment. A tensions created between the figure and the implements expose the lurking hostilities of the early 1990s.

Nilima Sheikh’s Shamiana. The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998. Installation view. Barbican Art Gallery. 5 October 2024 – 5 January 2025 © Eva Herzog Studio / Barbican Art Gallery.

Lastly a video installation by Nalini Malani closes the exhibition in which moving image, projected on the walls and playing on monitors in tin trunks, considers the impact of India’s nuclear testing and links it to concerns around violence and forced displacement.

The overall presentation of this exhibition is interesting. The Barbican Gallery is windowless, and the art is deliberately displayed in a low-lit environment with the art spot lit. There are certain areas where this does not do justice to the work and takes away from the vibrancy and details of the works but much of the time the art glows.

The entire exhibition is presented with no wall texts hence it is imperative to get the free booklet which gives you the full details of what is on display. But due to the dimly lit rooms it is not always easy to read the booklet. As an alternative there is a qr code for the audio guide. Either way, one needs a torch or headphones to get the full experience. This kind of presentation is not for everyone.

The Imaginary Institution of India: Art 1975-1998. Nalini Malani, Remembering Toba Tek Singh, 1998. Installation view, World Wide Video Festival, Amsterdam, 1998. © Nalini Malani.

A useful timeline of social and political events in India between 1975 & 1998 is included in the guide for those unfamiliar with India’s history over these two decades. Additional atrocities are included in this summation of history which are not necessarily represented in the exhibition such as the efforts to control the country’s burgeoning population where the government employees with more than two children were coerced into sterilisation procedures. Seven million vasectomies and tubal ligations were performed nationwide with several hundred leading to death.

The exhibition deftly guides visitors through this tumultuous time in India’s history and is well worth a visit.

A specially curated film season, Rewriting the Rules: Pioneering Indian Cinema after 1970, will run alongside the exhibition from 3 October to 12 December 2024.

TOP TIP

There will be a weekend of free entry to this exhibition as part of a Centre-wide celebration of Indian art, music and culture. Click here to learn more.

PAY WHAT YOU CAN

The Barbican will be running two Pay What You Can slots per week, 5-8pm on Thursdays and Friday (last entry 7pm) with prices starting from £3.

Select the price you can pay and enjoy the exhibition. If you’re able to pay the standard ticket price, you’ll be helping to support their Visual Arts programme.

Date: 5 October 2024— 5 January 2025. Location: The Barbican, Silk Street, London, EC2Y 8DS. Price: from £20 +BF. Pay What You Can slots (Thursdays & Fridays). Late night Thursday & Friday 10am-8pm. Book now.

Words by Natascha Milsom

The Cinnamon Club had completely flown under the radar for me. It is in a pocket of London I rarely visit, and even if I did, the building’s exterior gives little indication of what’s inside. But now that I’ve discovered it, I already have plans to return with my husband - and in my mind, a list of friends I would recommend it to…