Anthony McCall: Solid Light at Tate Modern review

The Tate has been showing light as an artistic tool and in this vein McCall’s exhibition replaces Yayoi Kasama’s Infinity Room. He is well and truly back on the scene with four major shows, here at the Tate, the Guggenheim Bilbao, Sprüth Magers in London, and the Museum of Art Architecture and Design in Lisbon in the autumn.

Portrait of Anthony McCall at Tate Modern 2024. Photo © Tate (Josh Croll).

McCall is an influential artist who has upended the conventional passive viewing experience of cinema and pioneered a more immersive form of participation in his practice where the viewer becomes a collaborator.

For this exhibition the Tate dipped into their archives and used their 2005 purchase of his work Line Describing a Cone 1973 from which to mount this exhibition tracing McCall’s developing interest in film and space.

McCall entered the art scene in the early seventies as a pioneer of experimental cinema and installation art honing his skills during his involvement in London’s Independent film community then moving to New York in 1973 with his then love interest, performance artist Carolee Schneemann. At this time the American art scene was bubbling with ideas in the spheres of radical avantgarde film making and performance art by the likes of Andy Warhol, Michael Snow and Yoko Ono. But he pondered on his belief that performance art can only really becomes art if it is recorded.

Anthony McCall, installation view of Split Second (Mirror) I, 2018, Tate Modern, 2024. Photo © Tate (Josh Croll).

The exhibition starts with a room showing line drawings and the meticulous planning that goes into his solid light work. “At its heart every piece is a line drawing the drawings never go away and are embedded in the work and are what produce the 3 dimensions forms.” - Anthony McCall

The line drawings are followed by a room with his film Landscape for Fire performed to a small audience at dusk on 27 August 1972, on a disused airfield in North Weald. A carefully choreographed outdoor performance of participants in white uniforms lighting fires in a geometric grid formation against a soundtrack of foghorns, wind and burning. It is hard to discern where this piece sits in the exhibition, except that it demonstrates early recorded performance art and highlights McCall’s shift from conventional cinema to “art”.

His beams of light works were originally shown in old New York lofts previously used for light engineering, millinery, or sweatshops. All being places with enough dust in the air to catch the light as well as numerous people smoking, as was allowed back then. The combination of the dust and smoke gave solidity to the projections hence did not lend itself well to being shown in clean slick galleries leading to the failure to reproduce the effect at an exhibition in Sweden. This combined with the realisation he needed to make a living led him to retreat from making art in the late 70s only to return to the practice in the new millennium enticed by the artistic potential of emerging technology. This explains the gap between his Line Describing a Cone piece (1973) and his next piece Doubling Back (2003).

The fun begins in the darkened main room beginning with his foundational work and three additional works of large-scale, immersive sculptural light installations. Upon entering you find yourself pondering the strong white lines drawn by projectors on black walls and realise the lines are slowly moving, then one notices the mist is making the beams of light solid and that gallery visitors are beginning to interact with the art. Each person is having their own unique experience and creating their own piece of “performance art”.

Anthony McCall installation view of Landscape for Fire, 1972, Tate Modern, 2024. Photo © Tate (Josh Croll).

Split-Second Mirror (2018), the most recent work on show, is the first time McCall has used an intervention using a wall sized mirror creating a double projection. When you are inside one of the cones you are looking at half of what is actually there, and the other half is virtual and you cannot tell with ease which is which.

There is an importance to the “slowness’ of his work. Everything moves intentionally slowly. If you make a sculpture form and it is moving fast the natural tendency is to stay stock still and watch it whereas if you make it move slowly it is almost as if you are looking at a sculpture that is not changing, and the visitor brings the movement to it. As McCall said, “The spectator should be the fastest object in the room.”

There is no prescribed way to enjoy the art. It is the job of the spectator to find ways to engage with the work and bring their own meaning and experiences to it. Find what you want from it. Stay as long or as little as you wish, and that freedom is as it should be.

Date: 27 June 2024 – 27 April 2025. Location: Tate Modern, Bankside, London SE1 9TG. Price: £14 Under 12s & Members FREE. Book now.

Words by Natascha Milsom

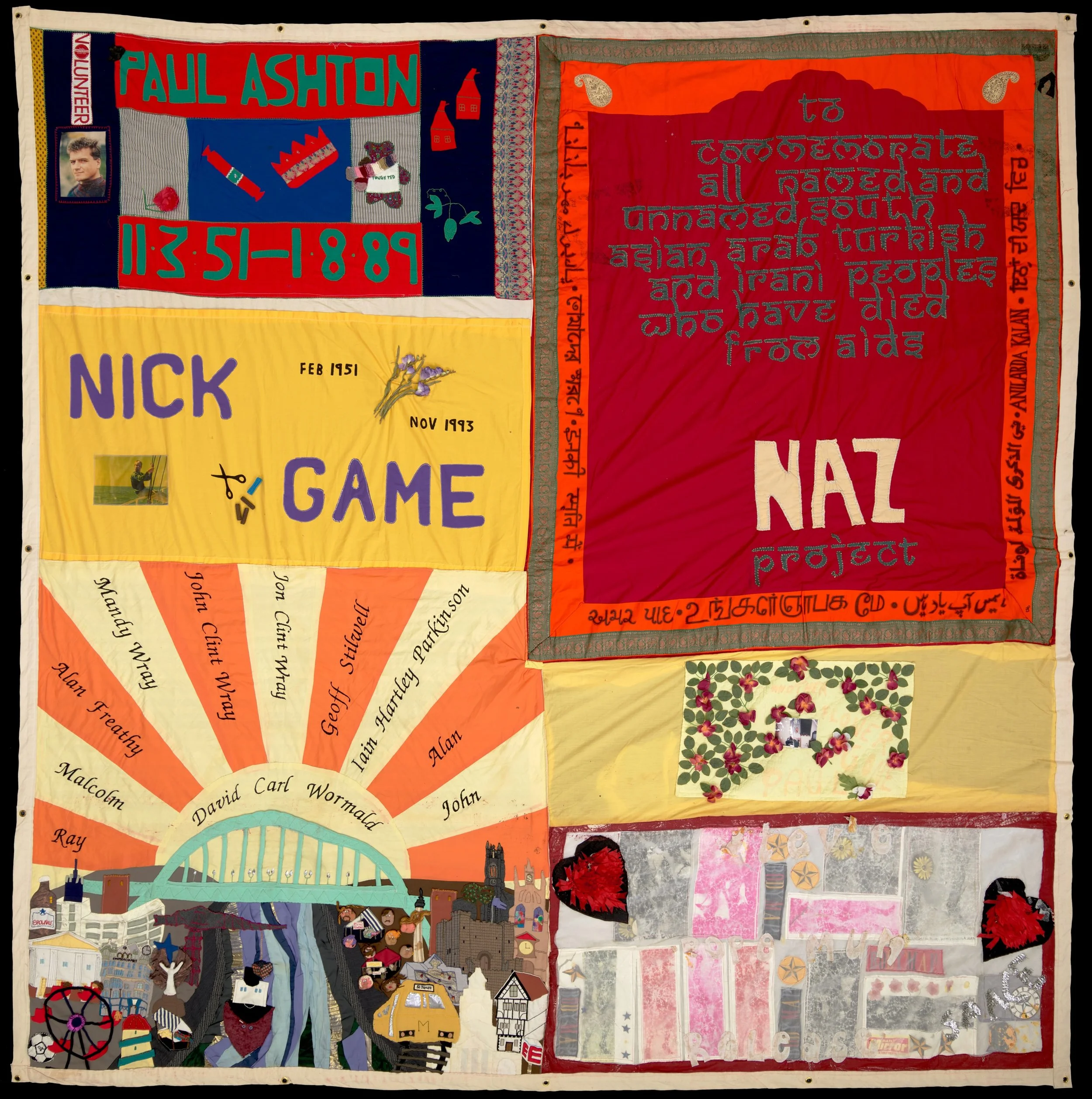

Tate will offer visitors a rare opportunity to view the UK AIDS Memorial Quilt in its Turbine Hall from 12 to 16 June 2025. The quilt, which began in 1989, consists of 42 quilts and 23 individual panels representing 384 individuals affected by HIV and AIDS…

Rosie Kellett debut cookbook, In for Dinner by , set for release on 1 May 2025 and available for pre-order now, is a heartfelt and practical guide to everyday cooking. Drawing on her own experiences of moving to London alone…

Discover what’s happening in London from 21–27 April, with major events including the new Multitudes arts festival at Southbank Centre, Brick Lane Jazz Festival, and the London Marathon…

What’s On in London This Week: Discover rooftop games at Roof East, cherry blossoms at the Horniman Gardens, and Easter fun at Hampton Court Palace. Plus, catch Loraine James live, Dear England at the National Theatre, and jazz nights at Ladbroke Hall…

London is set to showcase a rich and varied programme of art exhibitions this May. Here is our guide to the art exhibitions to watch out for in London in May…

With summer around the corner, what better way to spend a sunny day than by enjoying art, culture, and a bit of al fresco dining? Whether you’re looking for a peaceful spot to reflect on an exhibition or simply want to enjoy a light meal in the fresh air, here’s our guide to some of the best museum and gallery cafés with outdoor terraces in London….

As summer arrives in London, there’s no better time to embrace the city’s vibrant outdoor dining scene. Here is our guide to the best outdoor terraces to visit in London in 2025 for an unforgettable al fresco experience…

Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2025 · Gabriel Moses: Selah · Eileen Perrier: A Thousand Small Stories · Dianne Minnicucci: Belonging and Beyond · Linder: Danger Came Smiling · The Face Magazine: Culture Shift · Cecil Beaton’s Fashionable World · Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2025 · Photo London 2025 · Taylor Wessing Photo Portrait Prize · Nature Study: Ecology and the Contemporary Photobook · Flowers – Flora in Contemporary Art & Cultur…

This April, Ladbroke Hall’s renowned Friday Jazz & Dinner series returns, showcasing an impressive roster of artists at its Sunbeam Theatre. Each evening pairs exceptional live jazz with a carefully crafted menu from the award-winning Pollini restaurant…

Holly Blakey: A Wound with Teeth & Phantom · Kit de Waal: The Best of Everything · Skatepark Mette Ingvartsen · Spring Plant Fair 2025 · Hampton Court Palace Tulip Festival 2025 · Loraine James – Three-Day Residency · Jan Lisiecki Plays Beethoven · Carmen at The Royal Opera House · Cartier Exhibition · The Carracci Cartoons: Myths in the Making · Nora Turato: pool7 · Amoako Boafo: I Do Not Come to You by Chance · Bill Albertini: Baroque-O-Vision Redux…

Robyn Orlin had her first encounter with the rickshaw drivers of Durban at the young age of five or six, an experience that left such a deep impression on her that she later sought to learn more about their fate. Rickshaws were first introduced to Durban in 1892…

Murder She Didn’t Write is misbehaviour live on stage peppered with self-awareness and unbelievably good writing. This isn't a fad, this isn't sloppy - it’s naughty and scathingly witty…

Gagosian presents I Do Not Come to You by Chance, a powerful solo exhibition by Amoako Boafo at their Grosvenor Hill gallery this April 2025…

TOZI, derived from the affectionate Venetian slang for “a close-knit group of friends,” is the brainchild of an Italian trio that met while opening Shoreditch House under the Soho House Group. In 2013, Chef Maurilio Molteni, fresh from his time as Head Chef at Shoreditch House and developing the menu at Cecconi’s, opened the first TOZI restaurant in London…

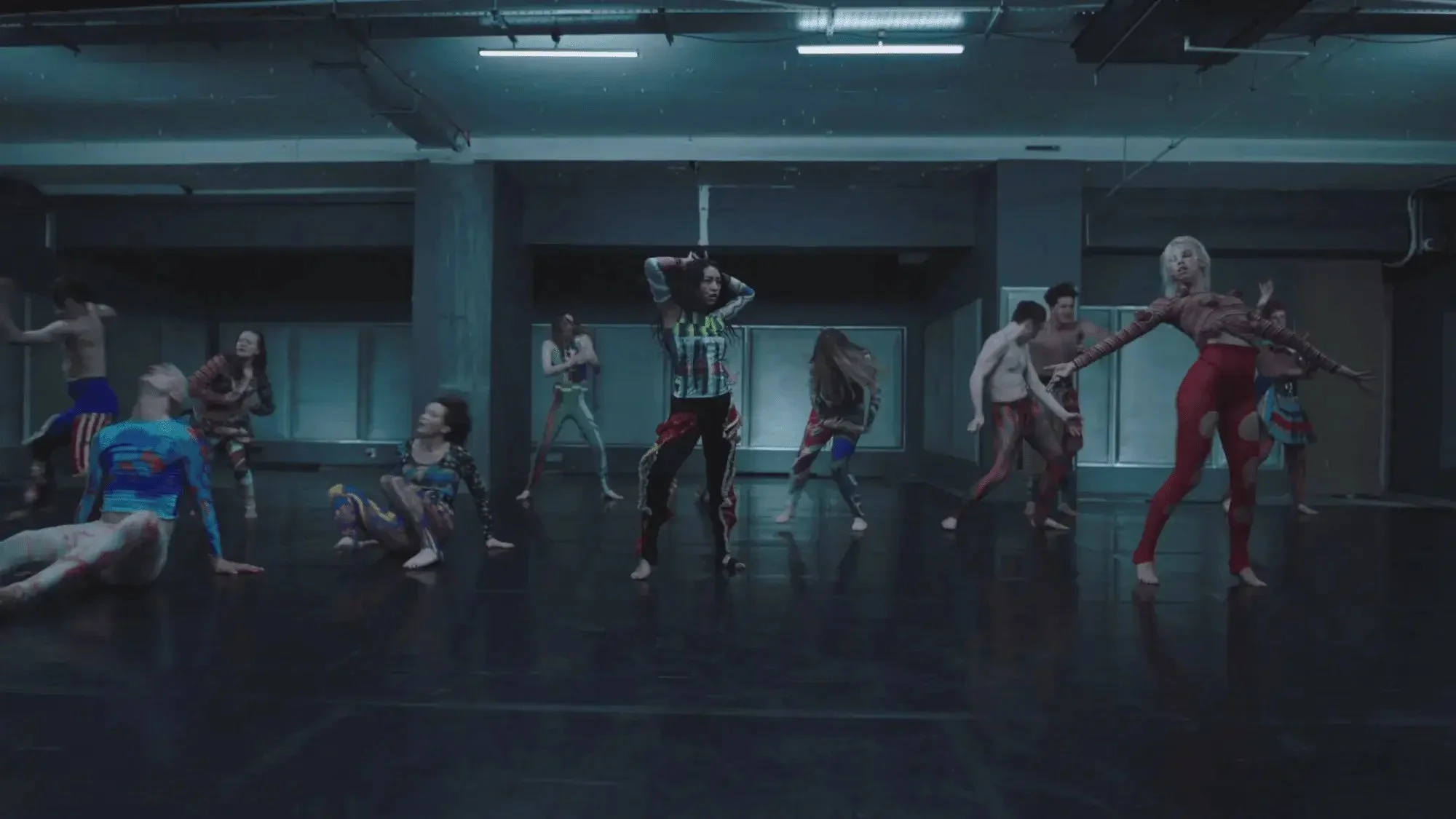

Multitudes at Southbank Centre will reimagine live music through bold collaborations across dance, theatre, and visual arts…

Multitudes Festival · Ed Atkins, Tate Britain · Brick Lane Jazz Festival · Teatro La Plaza’s Hamlet · Holly Blakey: A Wound with Teeth & Phantom · Roof East · Hampton Court Palace Tulip Festival 2025 · London Marathon 2025 · ROOH – Within Her · Sultan Stevenson Presents El Roi · Carmen at The Royal Opera House · The Big Egg Hunt 2025 · Architecture on Stage: New Architects · The Friends of Holland Park Annual Art Exhibition 2025

Autumn 2025 will bring two exciting exhibitions to the Barbican: ‘Dirty Looks’, a bold fashion exhibition exploring imperfection and decay, and an innovative art installation by Lucy Raven in The Curve…

Robyn Orlin: We wear our wheels with pride · Architecture on Stage: Lütjens Padmanabhan · Jay Bernard: Joint · Black is the Color of My Voice · Joe Webb Trio · Rhodri Davies at Cafe OTO · Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award 2025 · Lyon Opera Ballet: Cunningham Forever · AVA London · Sister Midnight · Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo · Eunjo Lee · Arpita Singh: Remembering · Fiona Banner aka The Vanity Press: Disarm · Bunhead Bakery · Time & Talents

Looking for something truly special this Mother’s Day? There are a variety of unique gifts and experiences to take advantage of in London, whether your mother loves exploring world-class art galleries and museum exhibitions, wandering through historic homes filled with fascinating stories and remarkable collections, indulging in a luxurious spa treatment, or enjoying an unforgettable dining experience..

After 18 successful years at Edinburgh Fringe, The Big Bite Size Show arrives in London for the first time at The Pleasance Theatre, no less. A gem of a place for fringe theatre in London…

180 Studios will present the largest showcase of photographer and filmmaker Gabriel Moses’ work to date, featuring over 70 photographs and 10 films in March…

Cartier Exhibition at the V&A · Giuseppe Penone: Thoughts in the Roots · Antony Gormley: WITNESS · Richard Wright at Camden Art Centre · The Carracci Cartoons: Myths in the Making · Eileen Perrier: A Thousand Small Stories · Ed Atkins at Tate Britain · Richard Hunt: Linear Peregrination · Nolan Oswald Dennis at Gasworks · Nora Turato: pool7 · In House: Ree Bradley and Pete Gomes at Studio Voltaire…

The Shirley Sherwood Gallery of Botanical Art at Kew Gardens will showcase new botanical works, cinematic installations, and the connections between artists and trees…

Orchid Festival · Alice Sara Ott: John Field & Beethoven · Our Mighty Groove at Sadler’s Wells East · Seth Troxler at Fabric · North London Laughs – A Charity Comedy Night · London Symphony Orchestra: Half Six Fix – Walton · In Focus: Amir Naderi · Artist Talk: Citra Sasmita - Into Eternal Land · Noah Davis at Barbican · Theaster Gates: 1965: Malcolm in Winter: A Translation Exercise · Ai Weiwei: A New Chapter · Galli: So, So, So · Somaya Critchlow: The Chamber

An important exhibition has opened at the National Gallery co-organised with the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Mayor of Siena, Nicoletta Fabio was in attendance on opening day to mark the exhibitions significance. Normally a major exhibition would take two to three years to come to fruition, in this instance, it has been in the making for eight year…

The Cinnamon Club had completely flown under the radar for me. It is in a pocket of London I rarely visit, and even if I did, the building’s exterior gives little indication of what’s inside. But now that I’ve discovered it, I already have plans to return with my husband - and in my mind, a list of friends I would recommend it to…