Is Facebook doing enough to tackle hate speech and misinformation?

It’s no secret that Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook, has been under intense, long-term scrutiny for how the platform responds to hate speech (defined by Facebook as ‘a direct attack on people based on what we call protected characteristics – race, ethnicity, national origin, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, caste, sex, gender, gender identity and serious disease or disability’) and misinformation (information that is deliberately designed to mislead the reader or is false in its nature) posted by its users. Though Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been introduced to detect extremist content, hateful material still exists on Facebook. In the midst of the recent protests against the killings of black people by police officers, the volume of material still accessible on these platforms has become even more evident.

Speaking at Georgetown University, Washington, in 2019, Zuckerberg stated: ‘We are at another crossroads. We can either continue to stand for free expression, understanding its messiness, but believing that the long journey towards greater progress requires confronting ideas that challenge us, or we can decide that the cost is simply too great and I’m here today because I believe that we must continue to stand for free expression.’ However, what Zuckerberg fails to understand is that sometimes, ideas are hateful and are not intended for ‘free expression’ but as hurtful content with insidious intent. Additionally, content can be uploaded to mislead shown by the recent posts made by President Donald Trump.

In late May, President Trump posted on Facebook and Twitter: ‘There is NO WAY (ZERO!) that Mail-In Ballot will be anything less than substantially fraudulent. He followed the tweet up with: ‘This will be a Rigged Election’. Prior to these posts being made, Twitter rolled out a new feature in which tweets could be labelled as potentially misleading in response to misinformation being published about COVID-19. The feature appears under tweets that are suspected to be incorrect and allows users to click on the button for more information on why it has been branded. In response to President Trump Twitter added the feature to the tweet to highlight to users that it contained potential misinformation and should be fact checked. Although President Trump made the same post on both Facebook, the company did nothing to flag the content as being potentially misleading.

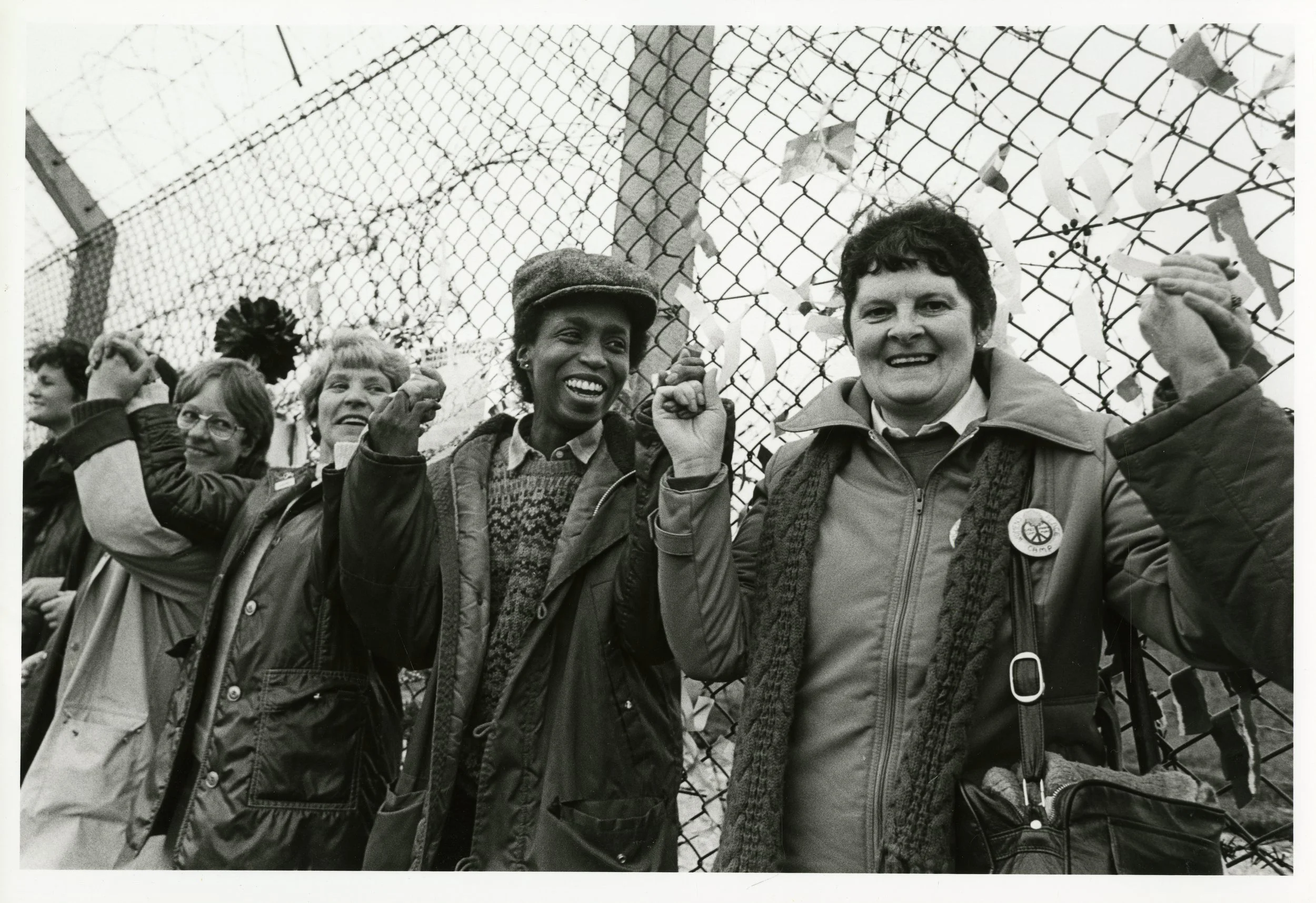

Additionally, Facebook came under fire for not removing a more recent post written by the President, ‘When the looting starts, the shooting starts’, which was posted in response to protests over the murder of George Floyd. The phrase is a direct connection to a comment made by Walter E. Headley, a former police chief of Miami, Florida, in response to violence that took place in 1967 around the Civil Rights Movement. In an interview with CNBC, Zuckerberg stated: ‘I don’t think that Facebook or internet platforms should be arbiters of truth’, seemingly ignoring the violent sentiment of Trump’s posts.

In a similar vein, Facebook has been criticised for its handling of comments made by media personality Katie Hopkins on her Instagram account, another social media platform owned by Facebook.

Earlier this year, Twitter made the decision to remove Hopkins from its platform after a petition signed by over 75,000 people circulated asking for her account to be suspended. Twitter released a statement saying: ‘Keeping Twitter safe is a top priority for us. Abuse and hateful conduct have no place on our service and we continue to take action where our rules are broken.

‘In this case, the account has been permanently suspended for violations of our hateful conduct policy.’

Despite the same content being posted on Hopkins’s Twitter and Instagram accounts, she remains an active member of the Instagram community and has faced no consequences from the company.

However, a turning point has arrived with many big brands pausing advertising on Facebook in an attempt to force the company to take more action against hate speech. The campaign’s website reads: ‘What would you do with $70 billion? We know what Facebook did. They allowed incitement to violence against protestors fighting for racial injustice in the wake of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, Ahmaud Arbery, Rayshard Brooks and so many others.’

The Stop Hate for Profit campaign has provided ten recommendations for Facebook and has encouraged brands such as Unilever and Hershey’s to stop their advertising campaigns on the platform. The boycott is a message to Facebook to do more to tackle hate speech online further shown by Stop Hate for Profit’s comments: ‘Could they protect and support Black users? Could they call out Holocaust denial as hate? Could they help get out the vote? They absolutely could. But they are actively choosing not to do so.’

With ad sales being Facebook’s primary source of revenue, the company now stands at a crossroads. As someone with significant influence in the tech sphere, Mark Zuckerberg will be forced to make a decision. Will he use his power to tackle hate speech on the platform using more definitive measures? Or will he continue to give a voice to misleading and hateful voices? As the ad boycotts continue, only time will tell which path Zuckerberg will choose.

Words by Emma Chadwick